King Crimson Fallen Angel: The Heart-Wrenching Tale of Brotherhood and New York Gang Violence

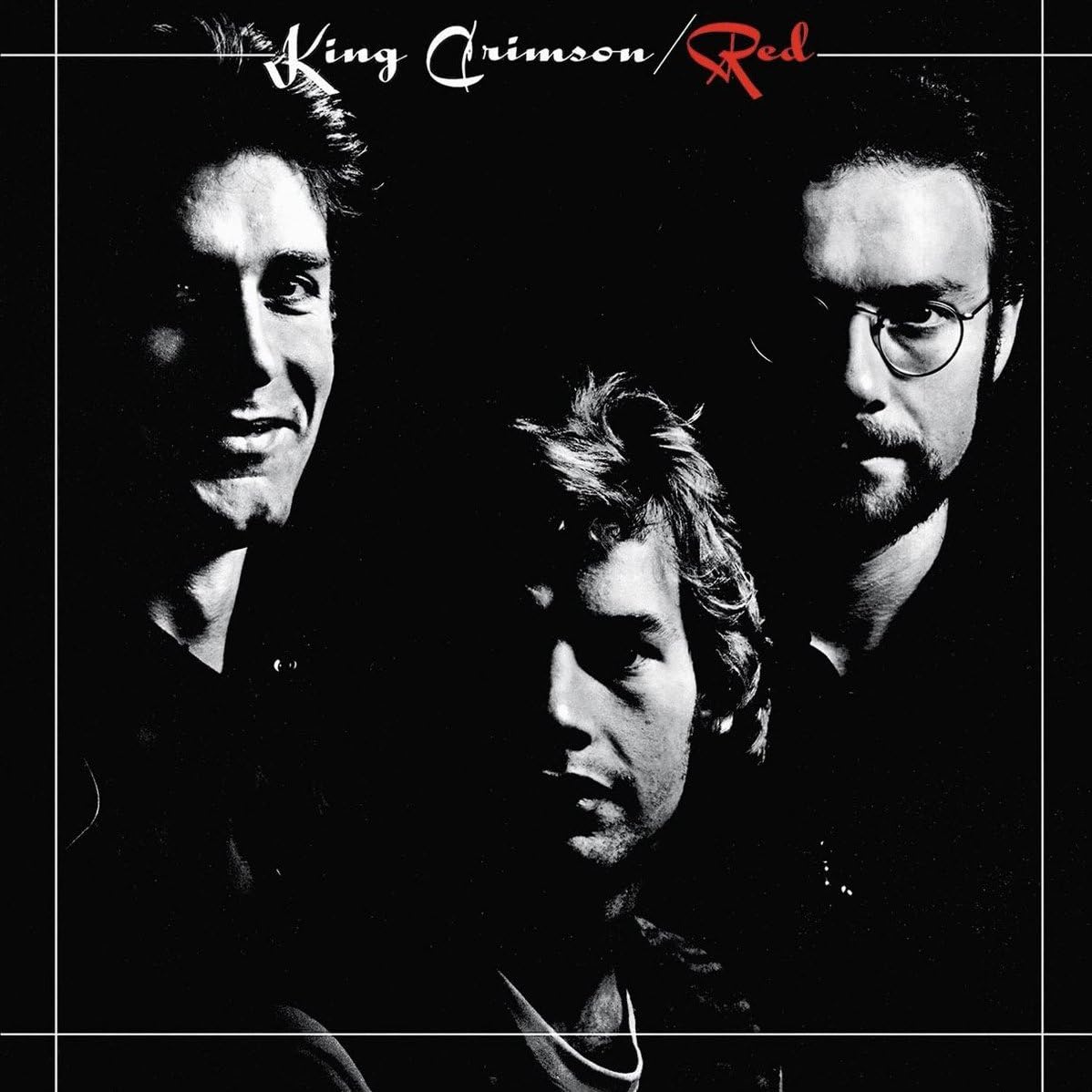

King Crimson Fallen Angel stands as one of progressive rock’s most emotionally devastating songs, a tragic narrative about a young man stabbed to death in New York City gang violence, delivered with profound pathos by bassist and vocalist John Wetton on the band’s 1974 masterpiece Red.

Ranked number 268 all-time on Rate Your Music with a 4.58 rating from over 5,500 listeners, this composition showcases a rare vulnerability in King Crimson’s catalog, balancing beautiful acoustic guitar passages with heavy electric sections while guest musicians Mark Charig on cornet and Robin Miller on oboe add classical sophistication to the arrangement.

If you’ve ever wondered how progressive rock could convey genuine human tragedy without sacrificing musical complexity, or why Fallen Angel represents Fripp’s final use of acoustic guitar on a King Crimson studio album, you’re about to discover one of the band’s most perfectly crafted and emotionally honest compositions.

The song originated from improvisations during the Larks’ Tongues in Aspic sessions in 1972, with Robert Fripp’s arpeggiated guitar motif finding its proper home two years later paired with Richard Palmer-James’s devastating lyrics about brotherhood, violence, and irreversible loss.

Let’s explore this baroque-influenced prog rock ballad that proves King Crimson could break hearts as effectively as they could shatter eardrums.

🎵 Experience Fallen Angel’s Full Orchestration

50th Anniversary Edition Now Available: The 2024 reissue features Steven Wilson’s new stereo remix revealing every detail of Robin Miller’s oboe harmonies and Mark Charig’s strident cornet, plus David Singleton’s elemental mix showcasing the isolated instrumentation without vocals or drums.

Hear John Wetton’s emotionally devastating vocal performance with unprecedented clarity, discover Robert Fripp’s acoustic guitar work shining like polished gems, and experience the lush cello and double bass arrangements that make Fallen Angel a prog rock masterpiece. This is the definitive version of one of King Crimson’s most emotionally powerful songs.

📋 Table of Contents [+]

Fallen Angel Overview: From Improvisation to Tragic Narrative

King Crimson Fallen Angel represents a remarkable transformation from abstract musical improvisation into focused narrative songcraft. The composition’s journey from experimental jam to emotionally devastating ballad demonstrates how King Crimson refined their creative process, allowing spontaneous musical ideas to gestate over years before finding their proper lyrical and thematic context.

At 6 minutes and 2 seconds, Fallen Angel is the shortest track on the Red album, yet it packs tremendous emotional impact into its concise runtime. The song serves as a crucial counterpoint to the instrumental heaviness of the title track Red and the extended epics Providence and Starless, providing a moment of vulnerability and human connection amid the album’s darker, more abstract compositions.

The track’s placement as the second song on Red strategically follows the aggressive opener, allowing listeners to catch their breath while simultaneously deepening the emotional stakes. After Red’s relentless instrumental assault, Fallen Angel’s acoustic opening and John Wetton’s tender initial verses create stark contrast that makes the song’s eventual heavy sections even more impactful.

Fallen Angel quickly became recognized as one of King Crimson’s most accessible yet sophisticated compositions, demonstrating that progressive rock could address real-world tragedy without resorting to simplistic musical treatments. The song balances baroque pop sensibilities with prog rock complexity, creating something that appeals to both casual listeners and genre devotees.

Origins in Larks’ Tongues in Aspic Sessions

The musical foundation of King Crimson Fallen Angel originated during improvisation sessions in 1972 when King Crimson recorded Larks’ Tongues in Aspic as a five-piece lineup including percussionist Jamie Muir and violinist David Cross. Robert Fripp developed an arpeggiated guitar motif during these sessions that caught the band’s attention but didn’t find immediate application in that album’s compositions.

This arpeggio pattern, characterized by its melodic sophistication and emotional resonance, remained in Fripp’s compositional vocabulary for two years before being revived for the Red sessions. The motif’s survival through multiple lineup changes and two intervening albums demonstrates its inherent strength and Fripp’s recognition that strong musical ideas deserve patience in finding their proper context.

The transition from a quintet’s improvisation to a power trio’s composed arrangement necessitated substantial reworking of the original concept. Without David Cross’s violin and Jamie Muir’s percussion to fill sonic space, the Red-era trio relied more heavily on guitar overdubs, guest orchestration, and careful production to realize the composition’s full potential.

This lengthy gestation period from 1972 improvisation to 1974 recording demonstrates King Crimson’s unique creative methodology, where musical ideas could exist in provisional forms for extended periods before crystallizing into final compositions. Many progressive rock bands composed linearly, but King Crimson maintained a reservoir of musical motifs that could be drawn upon when the right lyrical and thematic concepts emerged.

Fripp’s Final Acoustic Guitar Appearance

King Crimson Fallen Angel holds historical significance as the last King Crimson studio track to feature Robert Fripp playing acoustic guitar, with the sole exception of Adrian Belew’s acoustic version of “Eyes Wide Open” on the 2002 EP Happy with What You Have to Be Happy With. This makes Fallen Angel a culmination of Fripp’s acoustic work that had appeared periodically throughout King Crimson’s first five years.

Fripp’s acoustic guitar appears prominently during the song’s verses, providing delicate counterpoint to John Wetton’s bass and creating intimate space for the vocals. The acoustic’s bright, shimmering tone contrasts beautifully with the heavier electric sections, and the 2021 instrumental version released by King Crimson particularly highlights how the “glittering harmonics of the acoustic guitar really shine like polished gems.”

The decision to essentially retire acoustic guitar from King Crimson’s palette after Red reflects the band’s evolution toward heavier, more electric-focused sounds. When King Crimson reformed in 1981 with the Discipline lineup, they embraced a completely electric aesthetic influenced by new wave and art rock rather than the pastoral folk elements that had characterized early albums like Islands.

The acoustic guitar’s presence on Fallen Angel connects the song to King Crimson’s past while simultaneously functioning as a farewell to that aspect of their sound. This bittersweet quality reinforces the song’s themes of loss and endings, making the musical choices resonate with the lyrical content in ways that feel almost prophetic given the band’s impending dissolution.

Lyrics Analysis: A Brother’s Tragic Death

The lyrics of King Crimson Fallen Angel, written by Richard Palmer-James in collaboration with John Wetton, tell a heartbreaking story of brotherhood torn apart by urban gang violence. The narrative unfolds from the perspective of a man lamenting his younger brother’s death, stabbed on the streets of New York City after joining a gang, creating one of progressive rock’s most emotionally direct and devastating lyrical statements.

Unlike many prog rock lyrics that favor fantasy, science fiction, or abstract imagery, Fallen Angel confronts real-world tragedy with unflinching honesty. The specificity of the setting, the snow white side streets of cold New York City stained with blood, grounds the song in tangible reality that makes the emotional impact more immediate and visceral than typical prog metaphors would allow.

The song’s emotional power derives partly from its restraint. Palmer-James and Wetton avoid melodrama or exploitation, instead presenting the tragedy with dignity and focusing on the survivor’s grief and confusion. The repeated question “strangely why his life not mine” captures the guilt and incomprehension that accompanies losing a loved one to violence, a universal feeling that transcends the specific circumstances.

The Narrative of Gang Violence

King Crimson Fallen Angel opens with “tears of joy at the birth of a brother, never alone from that time,” establishing the deep bond between the siblings from infancy. This foundation makes the eventual tragedy more painful, as we understand these brothers grew up inseparable, facing “sixteen years through knife fights and danger” together before the fatal separation.

The lyrics progress from this innocent beginning through years of growing up in a dangerous urban environment where “knife fights and danger” are normalized parts of adolescence. This middle section establishes context without judgment, presenting gang life as a reality shaped by circumstance rather than inherent moral failing. The song acknowledges that “lifetimes spent on the streets of a city make us the people we are.”

The fatal moment arrives with shocking brevity and specificity: “switchblade stings in one tenth of a moment.” The speed of violence, how life ends in a fraction of a second, captures the arbitrary cruelty of street violence. The immediate shift to “better get back to the car” suggests the survivor’s dissociative shock, his mind unable to fully process what has just occurred and defaulting to practical concerns.

The repeated phrase “west side skyline crying, fallen angel dying” creates a chorus that universalizes the tragedy beyond one individual death. The skyline itself mourns, suggesting this violence affects the entire community, that every gang death diminishes the city itself. The “fallen angel” metaphor elevates the victim without sanctifying him, acknowledging both his humanity and his flawed choices.

Wetton’s Vocal Performance and Pathos

John Wetton’s vocal performance on King Crimson Fallen Angel ranks among his finest work in progressive rock, delivering Richard Palmer-James’s lyrics with what critics universally describe as “deep pathos.” Wetton’s naturally powerful voice, capable of cutting through the heaviest instrumental arrangements, here shows remarkable vulnerability and restraint during the quiet verses before unleashing its full emotional force in the choruses.

The verses feature Wetton singing almost conversationally, his voice intimate and close-miked, creating the impression of confession or remembrance. This vulnerable vocal approach contrasts dramatically with his more aggressive singing on tracks like “One More Red Nightmare,” demonstrating his range as a vocalist beyond simply projecting power and intensity.

During the chorus sections, Wetton’s voice swells with grief and anger, the words “fallen angel” delivered with increasing desperation across multiple repetitions. The vocal melody rises through these sections, Wetton pushing toward the upper end of his range in ways that convey emotional strain and breaking control, the sound of someone trying to hold themselves together while falling apart.

The final verse, describing the “snow white side streets of cold New York City stained with his blood it all went wrong,” carries particular weight in Wetton’s delivery. His phrasing of “sick and tired, blue wicked and wild, God only knows for how long” conveys exhaustion and resignation, the survivor recognizing that nothing will bring his brother back and that life simply continues despite impossible loss.

Snow White Side Streets of Cold New York City

The specific setting of King Crimson Fallen Angel in New York City gives the tragedy concrete geographical and cultural context. The phrase “snow white side streets of cold New York City” evokes winter in the city, the pristine white snow contrasting horrifically with blood, innocence stained by violence, beauty corrupted by death.

The west side skyline reference likely points to Manhattan’s West Side, historically associated with gang activity and portrayed in cultural works like West Side Story. This geographical specificity grounds the song in actual places where real tragedies occurred, making Fallen Angel feel less like artistic invention and more like documentation of lived experience or witnessed reality.

The cold emphasized in the lyrics operates on multiple levels: the literal cold of New York winter, the emotional coldness of a city where violence happens with terrible regularity, and the cold finality of death itself. This layered imagery demonstrates Palmer-James’s skill as a lyricist, using simple descriptive language to create multiple resonant meanings.

The urban setting also connects Fallen Angel thematically to concerns about violence, poverty, and social breakdown that dominated American discourse in the mid-1970s. New York City in 1974 faced fiscal crisis, rising crime rates, and declining infrastructure, making the song’s portrayal of urban danger feel contemporary and relevant to its original audience while remaining sadly timeless.

Musical Structure and Arrangement

King Crimson Fallen Angel employs a verse-chorus structure unusual for King Crimson but executed with enough sophistication and dynamic contrast to maintain progressive rock credibility. The song alternates between quiet, introspective verses featuring acoustic guitar and intense, heavy choruses where electric guitars and orchestration create dramatic impact, a dynamic approach that reinforces the lyrics’ emotional journey.

The composition begins with Robert Fripp’s arpeggiated acoustic guitar establishing the primary melodic motif, soon joined by Mellotron strings that add atmospheric depth. John Wetton’s bass enters subtly, providing harmonic foundation without overwhelming the delicate acoustic texture. This gentle opening creates intimacy that draws listeners into the narrative before the heavier sections arrive.

The verses maintain this relatively restrained character, with Bill Bruford’s drumming providing subtle pulse rather than assertive rhythmic drive. The drums here function almost like jazz accompaniment, responding to vocal phrasing and guitar lines rather than dominating the arrangement. This restraint makes Bruford’s occasional fills more impactful, punctuating emotional moments in the lyrics.

The transition from verse to chorus represents one of the song’s most effective musical moments, as the band suddenly shifts to heavy distorted guitars, assertive drumming, and the entrance of Mark Charig’s cornet. This dynamic shift mirrors the emotional shift from remembrance to grief, from past happiness to present loss, using volume and intensity as metaphors for overwhelming emotion.

Acoustic Guitar Arpeggios and Mellotron

The opening of King Crimson Fallen Angel features Robert Fripp’s acoustic guitar playing delicate arpeggios that establish the song’s melodic foundation. These arpeggios, fingerpicked rather than strummed, create a shimmering, harp-like quality that immediately distinguishes Fallen Angel from the aggressive electric guitar work on surrounding tracks like Red and One More Red Nightmare.

Fripp’s arpeggio pattern follows a specific intervallic structure that gives the song its distinctive character, neither conventionally major nor minor in feel but occupying ambiguous harmonic territory that reflects the lyrics’ emotional complexity. The pattern repeats throughout the verses with slight variations, providing continuity while allowing space for melodic development.

The Mellotron enters shortly after the acoustic guitar, playing sustained string sounds that add orchestral depth without overwhelming the intimate acoustic texture. Fripp’s Mellotron work here demonstrates his understanding of how to use the instrument as atmospheric enhancement rather than primary melody carrier, a restraint that serves the song’s emotional needs.

The combination of acoustic guitar and Mellotron strings creates what one reviewer described as a “baroque pop” quality, connecting Fallen Angel to 1960s pop sophistication while maintaining progressive rock complexity. This combination of influences demonstrates King Crimson’s ability to synthesize diverse musical traditions into coherent original compositions.

Dynamic Contrasts and Tempo Shifts

King Crimson Fallen Angel exploits dynamic contrast more effectively than perhaps any other song in the band’s catalog, using volume and intensity shifts to heighten emotional impact. The song moves from intimate quiet to overwhelming heaviness multiple times, each transition carefully crafted to reinforce lyrical content and maintain listener engagement through surprise and release.

The verses remain relatively quiet, with acoustic guitar, subtle bass, and restrained drums creating space for John Wetton’s vulnerable vocal delivery. This quietness makes listeners lean in, focusing attention on the lyrics’ narrative details and emotional nuances. The intimacy creates identification with the narrator’s grief, making the story feel personal rather than abstract.

The choruses explode in comparison, with distorted electric guitars entering suddenly alongside Mark Charig’s cornet and more aggressive drumming from Bill Bruford. These sections don’t simply increase volume but fundamentally change the song’s character, shifting from contemplation to catharsis, from remembering to mourning. The heaviness feels earned rather than gratuitous, musical emotion matching lyrical emotion.

The bridges between verse and chorus demonstrate particular sophistication, avoiding abrupt transitions that might feel jarring while maintaining clear demarcation between sections. Fripp and the band use brief instrumental passages to build tension before choruses and decompress after them, creating smooth emotional arcs that guide listener experience without manipulation.

The Heavy Chorus Sections

The chorus sections of King Crimson Fallen Angel feature some of the heaviest music on the Red album, with distorted electric guitars, powerful bass, thunderous drums, and Mark Charig’s cornet combining to create overwhelming sonic impact. These sections contrast dramatically with the verses’ gentleness, using musical weight to represent emotional weight, the crushing burden of grief made tangible through sound.

Robert Fripp’s electric guitar during choruses employs heavy distortion and sustained power chords rather than the intricate melodic lines he favors elsewhere. This relative simplicity serves the song’s needs perfectly, providing foundational heaviness that supports rather than competes with vocals and orchestration. The guitar acts as emotional reinforcement rather than technical display.

Bill Bruford’s drumming opens up during choruses, his normally complex rhythmic patterns giving way to more straightforward rock beats that emphasize the music’s power. His fills between vocal phrases add punctuation and drama, his cymbal crashes providing emphasis at key lyrical moments. The drumming here shows Bruford’s versatility, his ability to serve songs requiring direct impact rather than rhythmic complexity.

The repeated phrase “fallen angel” across multiple chorus repetitions builds through the song, each iteration featuring slightly different arrangement approaches and intensities. This variation prevents monotony while allowing the central phrase to accumulate emotional resonance through repetition, making it more rather than less powerful with each occurrence.

Classical Orchestration: Oboe and Cornet

King Crimson Fallen Angel features sophisticated classical orchestration through guest musicians Mark Charig on cornet and Robin Miller on oboe, both of whom had previously appeared on King Crimson’s 1970-1971 albums Lizard and Islands. Their return for Red creates continuity with King Crimson’s pastoral period while serving the new composition’s specific emotional and sonic needs.

The decision to include oboe and cornet rather than more conventional rock orchestration like strings or standard brass demonstrates King Crimson’s commitment to unusual instrumental colors. These instruments carry specific associations: oboe with pastoral melancholy and baroque music, cornet with both classical tradition and jazz expression, creating a unique sonic palette that distinguishes Fallen Angel from typical prog rock ballads.

The orchestration doesn’t simply add decoration to an already complete rock arrangement but functions as integral to the composition’s structure and emotional impact. Miller’s oboe and Charig’s cornet have distinct melodic roles, contributing counter-melodies and harmonic enrichment that make the song feel genuinely orchestrated rather than merely embellished.

Robin Miller’s Oboe Harmony

Robin Miller’s oboe playing on King Crimson Fallen Angel provides one of the song’s most distinctive and beautiful elements. His oboe melody, written by Robert Fripp during the Olympic Studios recording sessions, weaves through the verses and choruses providing counter-melody and harmonic support that enriches the acoustic guitar foundation without overwhelming it.

The oboe’s characteristic plaintive tone perfectly suits Fallen Angel’s melancholic character. Miller’s performance demonstrates remarkable sensitivity to dynamics and phrasing, his oboe sometimes barely audible beneath other instruments during verses before emerging more prominently during choruses where its distinctive timbre cuts through the heavier electric guitar texture.

The 2021 instrumental version released by King Crimson, which strips away vocals and drums, allows focus on Miller’s oboe line and reveals its melodic sophistication. Listeners can hear how Fripp’s composition for oboe creates dialogue with the acoustic guitar, the two instruments engaging in baroque-style counterpoint that adds intellectual satisfaction to the emotional impact.

Miller’s oboe appears during select musical passages rather than throughout the entire song, Fripp’s arrangement demonstrating restraint in deploying the instrument for maximum effect. This selective use makes the oboe’s appearances more impactful, its entries and exits creating additional structural markers that guide listener experience through the composition.

Mark Charig’s Strident Cornet

Mark Charig’s cornet playing on King Crimson Fallen Angel adds what one official release description calls “piquancy and heat,” particularly during the heavier chorus sections where his strident tone cuts through dense guitar and rhythm section textures. The cornet, a brass instrument similar to but distinct from trumpet, provides warmer tone and more lyrical quality than trumpet would offer.

Charig’s performance demonstrates jazz influences in its phrasing and improvisational feel, his lines following chord changes while maintaining melodic independence. The cornet doesn’t simply double vocal melodies or guitar lines but occupies its own space in the arrangement, sometimes answering John Wetton’s vocals, sometimes providing counter-melody, sometimes adding harmonic color through sustained notes.

The cornet’s prominence during chorus sections reinforces their emotional intensity, Charig’s playing adding a layer of expressiveness that pure electric guitar couldn’t provide. Brass instruments carry inherent associations with both military ceremony and jazz passion, both of which resonate with Fallen Angel’s themes of loss, honor, and overwhelming emotion.

The 2024 Steven Wilson remix and particularly the elemental mix by David Singleton reveal Charig’s cornet parts with unprecedented clarity, allowing listeners to appreciate the sophistication of his performance and its crucial role in the song’s overall impact. These new mixes demonstrate that what might sound like atmospheric texture actually contains specific melodic and harmonic content worthy of close attention.

Cello and Double Bass Foundation

King Crimson Fallen Angel features uncredited cello and double bass players who provide low-end orchestral support that reinforces John Wetton’s bass guitar while adding classical depth to the arrangement. These string players, their identities unknown but their contributions significant, create a massed bass sound during heavier sections that gives the music unusual weight and gravitas.

The cello and double bass function particularly prominently during the instrumental bridges and chorus sections, their sustained notes creating harmonic foundation that allows electric guitars and brass to operate melodically rather than solely providing rhythm and power. This orchestral approach to bass frequencies distinguishes Fallen Angel from typical rock arrangements where bass guitar alone handles low-end duties.

The 2021 instrumental version particularly reveals the cello and double bass contributions, described in the official release notes as creating a texture from which “the glittering harmonics of the acoustic guitar really shine like polished gems.” The orchestral strings provide dark contrast that makes the acoustic guitar’s brightness more apparent, demonstrating how thoughtful arrangement creates clarity through contrast.

The decision to include these classical string instruments connects Fallen Angel to King Crimson’s early albums, particularly Islands, which featured prominent classical orchestration. This connection creates thematic continuity within King Crimson’s catalog while serving the specific needs of Fallen Angel’s arrangement, showing how musical tradition can inform without constraining contemporary composition.

Recording at Olympic Studios

King Crimson Fallen Angel was recorded at Olympic Studios in Barnes, London, during July and August 1974, the same sessions that produced the entire Red album. Recording engineer George Chkiantz, who had worked with King Crimson on Starless and Bible Black, returned to capture the band’s performances and integrate the guest orchestral musicians into the power trio’s sound.

The recording sessions for Fallen Angel required particular care in balancing the acoustic and electric elements, the intimate vocals and heavy instrumentation, the rock rhythm section and classical orchestration. Chkiantz’s production demonstrates remarkable skill in creating coherent sound from these diverse elements, maintaining clarity while allowing each instrument its own sonic space.

Robert Fripp’s acoustic guitar required close miking to capture its delicate finger-picked arpeggios and ensure they remained audible when electric guitars, bass, drums, and orchestration entered during heavier sections. The acoustic’s recording quality directly affects the song’s success, as muddy or indistinct acoustic tone would undermine the verses’ intimacy and emotional impact.

John Wetton’s vocals received careful treatment to preserve their emotional nuance, particularly during quiet verse sections where his voice carries the narrative weight. The vocal recording captures Wetton’s dynamic range from tender vulnerability to powerful emotional release, allowing his performance to guide listener engagement and maintain the song’s dramatic arc.

The integration of Mark Charig’s cornet and Robin Miller’s oboe required overdubbing after the basic power trio tracks were recorded, with Fripp writing the oboe harmony during the session specifically to enhance the existing arrangement. This flexible, responsive approach to orchestration demonstrates King Crimson’s willingness to let compositions evolve during the recording process rather than arriving with completely predetermined arrangements.

Critical Reception and Fan Response

King Crimson Fallen Angel has received consistent praise from critics and fans as one of the most emotionally powerful and musically sophisticated songs in the progressive rock canon. Rate Your Music users rank it number 268 all-time across all genres and number 2 for 1974, with a 4.58 rating from over 5,500 listeners, demonstrating broad consensus about its quality and impact.

Contemporary reviews of Red generally highlighted Fallen Angel as a standout track, praising John Wetton’s vocal performance and the song’s effective balance of gentleness and power. Critics noted how the song provided necessary emotional relief within Red’s otherwise relentless heaviness, offering human connection and narrative coherence that made the instrumental tracks more impactful through contrast.

Modern reassessments continue to recognize Fallen Angel as essential King Crimson, with many fans and critics citing it as a favorite from the Red album despite the legendary status of tracks like the title song and Starless. The song’s accessibility, combined with its musical sophistication, makes it an ideal entry point for listeners new to King Crimson while satisfying longtime fans.

Fans particularly praise the song’s emotional honesty and Wetton’s vocal performance, with many comments focusing on how the song moves them emotionally rather than simply impressing them technically. This emotional response indicates Fallen Angel succeeds as genuine artistic expression rather than mere technical display, a distinction that separates great progressive rock from self-indulgent virtuoso exercise.

The orchestration receives special attention in discussions of Fallen Angel, with listeners often citing Mark Charig’s cornet and Robin Miller’s oboe as crucial elements that elevate the song beyond standard rock instrumentation. These classical touches demonstrate King Crimson’s ability to integrate diverse influences without sacrificing rock power or progressive complexity.

Live Performance History

King Crimson Fallen Angel was performed live during the band’s 1974 tour promoting Red, though less frequently than the instrumental tracks and One More Red Nightmare. The song’s intricate arrangement with acoustic guitar and the absence of orchestral musicians on tour made it more challenging to present than compositions built primarily around the power trio’s instrumentation.

Live versions of Fallen Angel maintained the studio arrangement’s essential structure while adapting to the limitations and opportunities of live performance. Without cornet and oboe, the trio had to fill those sonic spaces through creative use of Mellotron, guitar overdrive, and emphasis on the core melody that could be delivered by Fripp’s electric guitar in place of the orchestral instruments.

John Wetton’s vocal performances of Fallen Angel in concert reportedly maintained the emotional intensity of the studio version, his powerful voice capable of projecting the lyrics’ pathos even in large venues. The live setting added rawness to his delivery, the lack of studio polish making the emotional content feel even more immediate and genuine.

After King Crimson disbanded in September 1974, Fallen Angel disappeared from live performance for decades. When the band reformed in 1981 with Adrian Belew and different personnel, they focused primarily on new material and selected tracks from the first four albums, leaving most of the Red album untouched in setlists.

Fallen Angel has occasionally appeared in setlists by projects like the 21st Century Schizoid Band and in John Wetton’s solo performances, though less frequently than other King Crimson classics. The song’s specific association with Wetton’s vocals and the original arrangement makes it challenging for later configurations to reinterpret without Wetton’s distinctive voice.

Frequently Asked Questions About Fallen Angel

Conclusion: Fallen Angel’s Enduring Emotional Power

King Crimson Fallen Angel endures as one of progressive rock’s most emotionally honest and musically sophisticated ballads five decades after its creation, demonstrating that complex arrangement and genuine feeling aren’t mutually exclusive. The song’s tragic narrative, delivered with devastating pathos by John Wetton and enriched by baroque orchestration, creates an experience that moves listeners rather than simply impressing them.

The composition’s journey from 1972 improvisation to 1974 completed work demonstrates King Crimson’s unique creative process, where musical ideas could exist provisionally for years before finding proper context. Robert Fripp’s patience in allowing his arpeggiated guitar motif to gestate until paired with Richard Palmer-James’s tragic lyrics shows artistic maturity and understanding that strong concepts deserve time to find their fullest expression.

Fallen Angel’s significance as Fripp’s final acoustic guitar appearance on a King Crimson studio recording adds poignancy, making the song both a culmination of the band’s pastoral tendencies and a farewell to that aspect of their sound. The acoustic guitar’s shimmering presence throughout the verses creates beauty and intimacy that contrast powerfully with the heavy choruses’ overwhelming emotion.

The song proves progressive rock could address real human tragedy without sacrificing musical complexity or resorting to simplistic treatments. Fallen Angel’s sophisticated dynamics, classical orchestration, and careful arrangement serve rather than obscure the emotional core, creating art that satisfies both intellectually and emotionally, head and heart simultaneously engaged.

Ready to explore more King Crimson masterpieces?

Discover our complete analysis of Starless and the Red title track, explore 1970s progressive rock, or browse our album reviews!