After the gold rush arrived on September 19, 1970, and transformed Neil Young from promising artist to generational voice.

This third studio album emerged from Young’s Topanga Canyon basement during three feverish weeks of creativity.

Recorded on makeshift equipment with an 18-year-old pianist who’d never played professionally, after the gold rush became one of rock’s most acclaimed albums despite Rolling Stone initially dismissing it as half-baked.

This third studio album emerged from Young’s Topanga Canyon basement during three feverish weeks of creativity.

Recorded on makeshift equipment with an 18-year-old pianist who’d never played professionally, after the gold rush became one of rock’s most acclaimed albums despite Rolling Stone initially dismissing it as half-baked.

Table of Contents

- Album Overview: From Writer’s Block to After the Gold Rush Breakthrough

- Recording Sessions: The Topanga Canyon Basement Chronicles

- Musicians & Personnel: After the Gold Rush’s Unlikely Cast

- Track-by-Track Analysis: After the Gold Rush Song by Song

- Singles & Chart Performance: Commercial Reception

- Critical Reception: From “Half-Baked” to Masterpiece

- Musical Style & Themes: The Sound of Transition

- Album Artwork & Packaging: Solarized Greenwich Village

- Legacy & Influence: After the Gold Rush’s Enduring Impact

- Final Thoughts on This Essential Album

Experience Neil Young’s Basement Masterpiece

Own the album that features “Southern Man,” “Only Love Can Break Your Heart,” and the environmental anthem that inspired a generation.

Album Overview: From Writer’s Block to After the Gold Rush Breakthrough

After the gold rush represents Neil Young’s third studio album and first true solo masterwork.

Released through Reprise Records with catalogue number RS 6383, the album emerged during one of rock’s most fertile creative periods.

Young was simultaneously balancing commitments to Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young and his backing band Crazy Horse.

The album arrived mere months after CSNY’s chart-topping Déjà Vu, joining solo efforts from Stephen Stills, David Crosby, and Graham Nash.

All four CSNY members released solo albums within twelve months, each charting in the top fifteen.

Released through Reprise Records with catalogue number RS 6383, the album emerged during one of rock’s most fertile creative periods.

Young was simultaneously balancing commitments to Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young and his backing band Crazy Horse.

The album arrived mere months after CSNY’s chart-topping Déjà Vu, joining solo efforts from Stephen Stills, David Crosby, and Graham Nash.

All four CSNY members released solo albums within twelve months, each charting in the top fifteen.

The Dean Stockwell Screenplay That Broke the Dam

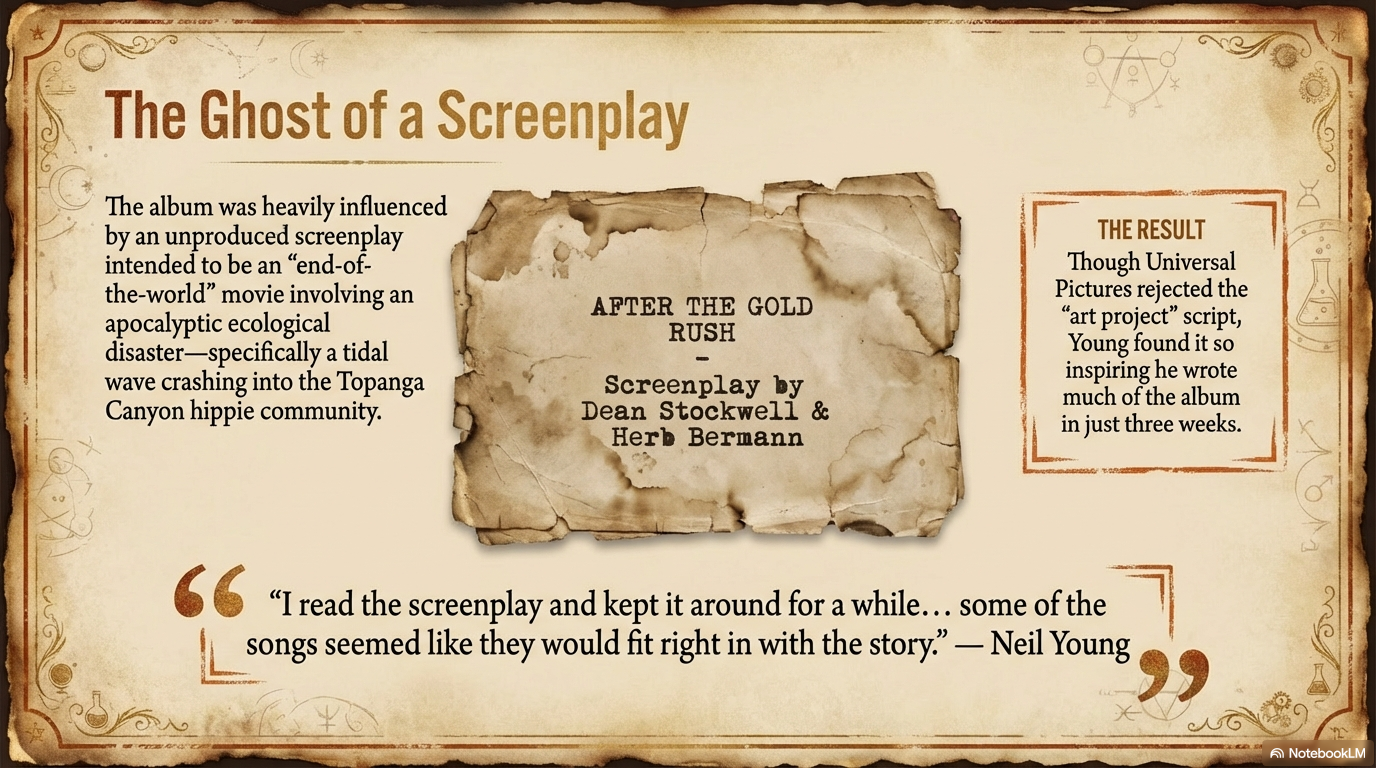

The catalyst for after the gold rush came from an unlikely source.

Actor Dean Stockwell had written a screenplay with Herb Bermann following encouragement from Dennis Hopper.

Fresh from Easy Rider’s success, Hopper urged Stockwell to create his own film project.

Stockwell retreated to Topanga Canyon and wrote a screenplay titled “After the Gold Rush.”

The plot centered on an apocalyptic ecological disaster washing away the Topanga Canyon hippie community.

Young, suffering from months of writer’s block, received a copy of the screenplay.

According to Stockwell, the screenplay sparked an immediate creative breakthrough.

Young wrote the entire album in just three weeks after reading the script.

“Neil was living in Topanga then too, and a copy of it somehow got to him,” Stockwell recalled.

“He had had writer’s block for months, and his record company was after him.”

Universal Studios showed initial interest but ultimately rejected the project as too artistic.

Only two songs directly reference the screenplay: the title track and “Cripple Creek Ferry.”

However, the apocalyptic themes and imagery permeate the entire album.

Actor Dean Stockwell had written a screenplay with Herb Bermann following encouragement from Dennis Hopper.

Fresh from Easy Rider’s success, Hopper urged Stockwell to create his own film project.

Stockwell retreated to Topanga Canyon and wrote a screenplay titled “After the Gold Rush.”

The plot centered on an apocalyptic ecological disaster washing away the Topanga Canyon hippie community.

Young, suffering from months of writer’s block, received a copy of the screenplay.

According to Stockwell, the screenplay sparked an immediate creative breakthrough.

Young wrote the entire album in just three weeks after reading the script.

“Neil was living in Topanga then too, and a copy of it somehow got to him,” Stockwell recalled.

“He had had writer’s block for months, and his record company was after him.”

Universal Studios showed initial interest but ultimately rejected the project as too artistic.

Only two songs directly reference the screenplay: the title track and “Cripple Creek Ferry.”

However, the apocalyptic themes and imagery permeate the entire album.

Release Timeline and Context

After the gold rush entered the Billboard Top Pop Albums chart on September 19, 1970.

The album peaked at number eight in October, establishing Young’s commercial viability.

This success proved particularly significant given the album’s sparse production and unconventional approach.

Young was 24 years old at the time of release.

The album followed two previous solo efforts: his 1968 self-titled debut and 1969’s Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere.

Those earlier albums received modest attention, but after the gold rush elevated Young’s status permanently.

The timing coincided with the pivotal shift from 1960s optimism to 1970s realism.

Environmental concerns, Vietnam War disillusionment, and social upheaval dominated the cultural landscape.

Young captured this transitional moment with remarkable precision.

The album peaked at number eight in October, establishing Young’s commercial viability.

This success proved particularly significant given the album’s sparse production and unconventional approach.

Young was 24 years old at the time of release.

The album followed two previous solo efforts: his 1968 self-titled debut and 1969’s Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere.

Those earlier albums received modest attention, but after the gold rush elevated Young’s status permanently.

The timing coincided with the pivotal shift from 1960s optimism to 1970s realism.

Environmental concerns, Vietnam War disillusionment, and social upheaval dominated the cultural landscape.

Young captured this transitional moment with remarkable precision.

Recording Sessions: The Topanga Canyon Basement Chronicles

The recording sessions spanned nearly a year, from August 1969 to June 1970.

Three different studios contributed to the final album.

Initial sessions occurred at Sunset Sound Studios in Hollywood during August 1969.

Young then moved recording to Sound City Studios for select tracks.

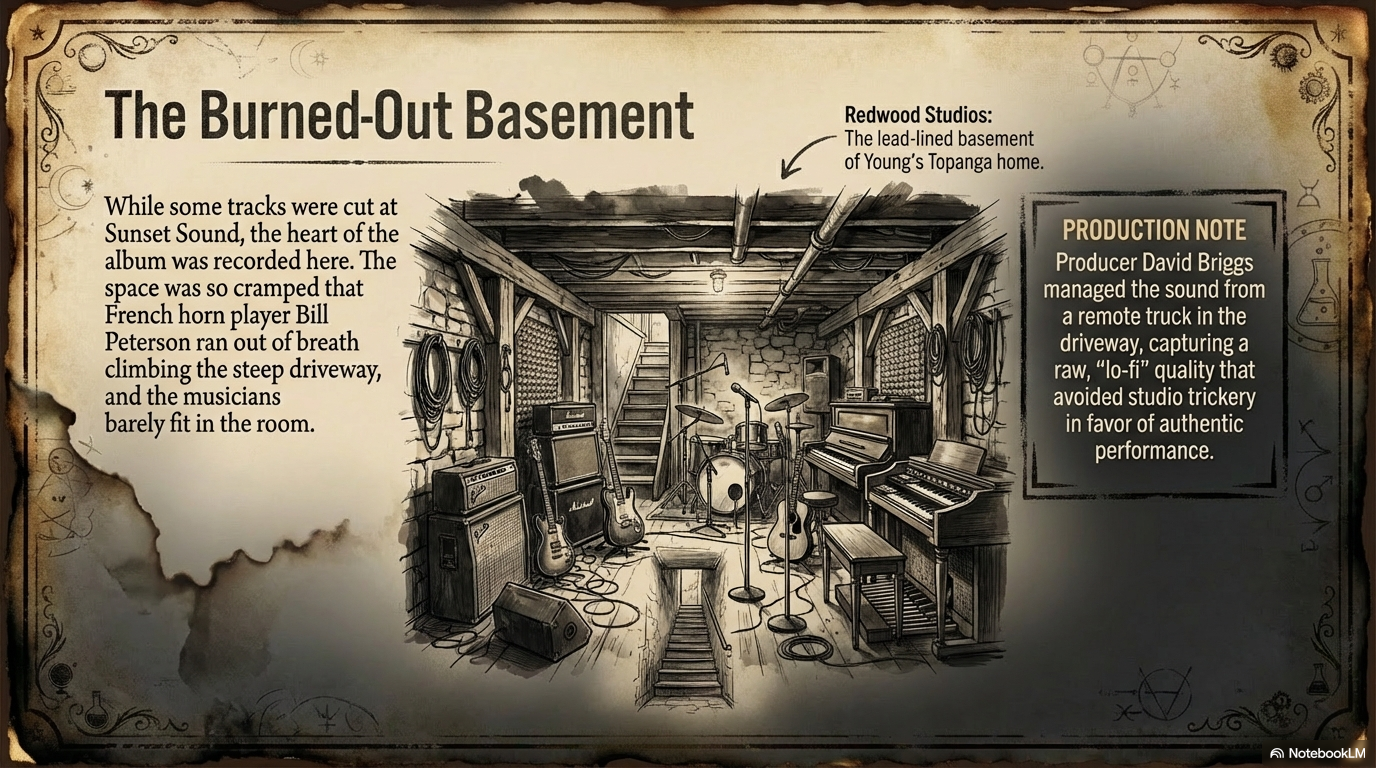

However, the bulk of after the gold rush emerged from Young’s home basement studio.

Young dubbed his makeshift recording space “Redwood Studios” in Topanga Canyon.

He personally installed wood paneling on the walls.

“I put the wood on the walls myself and loved that feeling,” Young remembered.

The house sat on a steep hillside overlooking the canyon.

Bill Peterson, the flugelhorn player, ran out of breath climbing Young’s driveway.

Three different studios contributed to the final album.

Initial sessions occurred at Sunset Sound Studios in Hollywood during August 1969.

Young then moved recording to Sound City Studios for select tracks.

However, the bulk of after the gold rush emerged from Young’s home basement studio.

Young dubbed his makeshift recording space “Redwood Studios” in Topanga Canyon.

He personally installed wood paneling on the walls.

“I put the wood on the walls myself and loved that feeling,” Young remembered.

The house sat on a steep hillside overlooking the canyon.

Bill Peterson, the flugelhorn player, ran out of breath climbing Young’s driveway.

The Sunset Sound Sessions

Young began with Crazy Horse at Sunset Sound Studios in August 1969.

These sessions followed the band’s North American tour supporting Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere.

Progress faced challenges due to rhythm guitarist Danny Whitten’s deteriorating health.

Nevertheless, the sessions yielded two album tracks.

“I Believe in You” captured Whitten’s haunting guitar work.

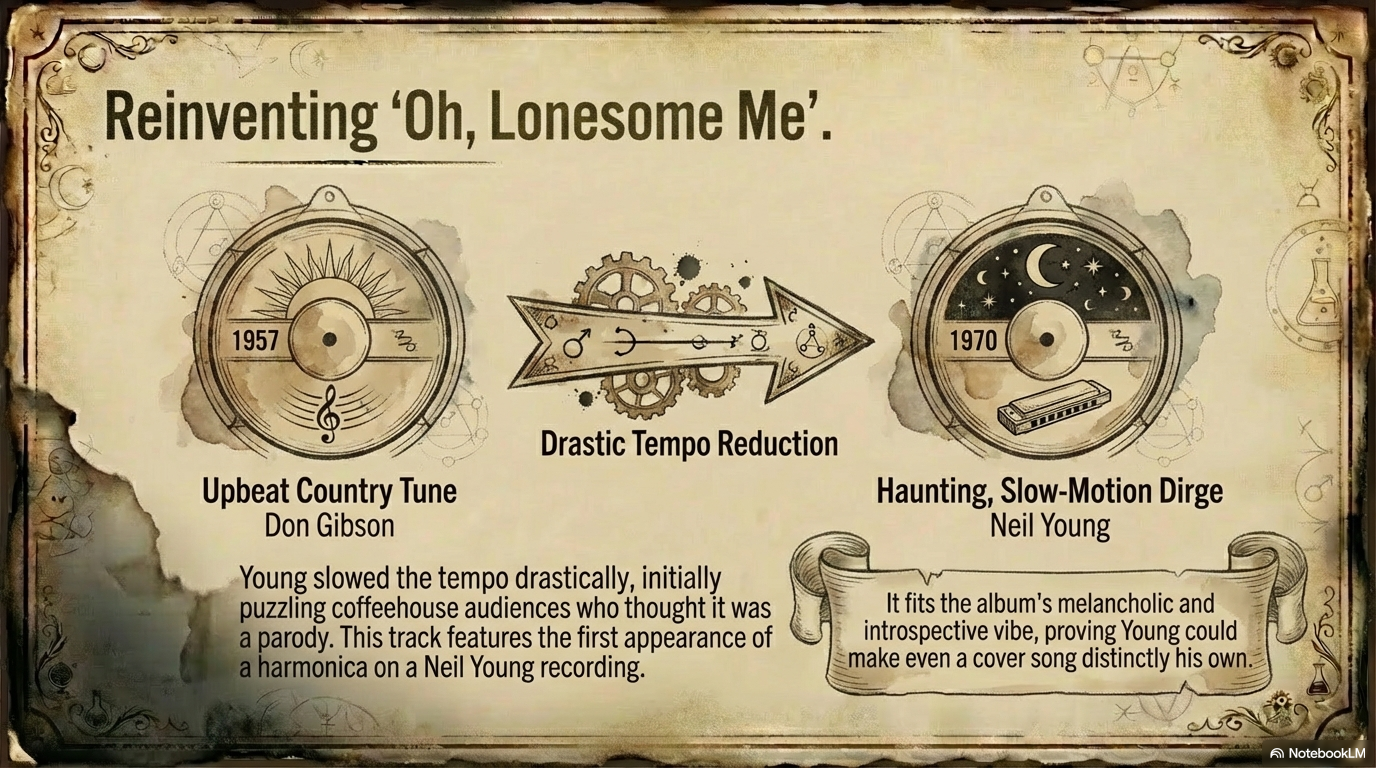

“Oh, Lonesome Me,” a Don Gibson cover, marked Young’s first recording with harmonica.

Young radically reimagined Gibson’s 1957 country hit with a somber folk arrangement.

The original version dated from Young’s Toronto coffeehouse days in late 1965.

“I had an arrangement of ‘Oh Lonesome Me’ that I really liked, and people laughed at it,” Young explained.

“Thinking it was a parody or something.”

“I used it on ‘After the Gold Rush’, and that worked.”

These sessions followed the band’s North American tour supporting Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere.

Progress faced challenges due to rhythm guitarist Danny Whitten’s deteriorating health.

Nevertheless, the sessions yielded two album tracks.

“I Believe in You” captured Whitten’s haunting guitar work.

“Oh, Lonesome Me,” a Don Gibson cover, marked Young’s first recording with harmonica.

Young radically reimagined Gibson’s 1957 country hit with a somber folk arrangement.

The original version dated from Young’s Toronto coffeehouse days in late 1965.

“I had an arrangement of ‘Oh Lonesome Me’ that I really liked, and people laughed at it,” Young explained.

“Thinking it was a parody or something.”

“I used it on ‘After the Gold Rush’, and that worked.”

The March 1970 Topanga Sessions

The album’s core emerged during mid-March 1970 in Young’s basement.

Producer David Briggs operated from a small control room adjacent to the recording space.

The studio was cramped, hot, and technically limited.

Yet these constraints fostered the album’s intimate, unpolished sound.

Young recorded seven songs during these concentrated sessions.

“Tell Me Why” opened the album with Young’s trademark falsetto.

“After the Gold Rush” featured Young solo on piano with Bill Peterson’s flugelhorn.

“Only Love Can Break Your Heart” combined acoustic intimacy with emotional weight.

“Southern Man” delivered Young’s most politically charged statement to date.

“Till the Morning Comes” lasted barely over a minute.

“Don’t Let It Bring You Down” captured existential depression with stark beauty.

“Cripple Creek Ferry” closed the album with playful brevity.

All tracks recorded on March 12, 15, 17, or 19, 1970.

Producer David Briggs operated from a small control room adjacent to the recording space.

The studio was cramped, hot, and technically limited.

Yet these constraints fostered the album’s intimate, unpolished sound.

Young recorded seven songs during these concentrated sessions.

“Tell Me Why” opened the album with Young’s trademark falsetto.

“After the Gold Rush” featured Young solo on piano with Bill Peterson’s flugelhorn.

“Only Love Can Break Your Heart” combined acoustic intimacy with emotional weight.

“Southern Man” delivered Young’s most politically charged statement to date.

“Till the Morning Comes” lasted barely over a minute.

“Don’t Let It Bring You Down” captured existential depression with stark beauty.

“Cripple Creek Ferry” closed the album with playful brevity.

All tracks recorded on March 12, 15, 17, or 19, 1970.

The Final Sessions

“When You Dance I Can Really Love” recorded in April 1970 at Young’s home.

This session marked the last time the original Crazy Horse lineup played together.

Danny Whitten had cleaned up temporarily and returned for the recording.

Jack Nitzsche joined on piano for this track only.

“Jack’s piano on that track is unreal,” Young later recalled.

“We were really soaring!”

The original group dynamic functioned magnificently during this brief reunion.

Whitten also overdubbed chorus vocals on multiple tracks, significantly improving them.

“Birds” came last, recorded on June 30, 1970, at Sound City Studios.

Young had attempted the song multiple times over two years.

An August 1969 electric version with vibes accidentally appeared on the “Only Love Can Break Your Heart” B-side.

Young also recorded an acoustic duet with Graham Nash.

The final album version featured Young on solo piano with Crazy Horse on vocals.

This version captured the song’s melancholic bird imagery perfectly.

This session marked the last time the original Crazy Horse lineup played together.

Danny Whitten had cleaned up temporarily and returned for the recording.

Jack Nitzsche joined on piano for this track only.

“Jack’s piano on that track is unreal,” Young later recalled.

“We were really soaring!”

The original group dynamic functioned magnificently during this brief reunion.

Whitten also overdubbed chorus vocals on multiple tracks, significantly improving them.

“Birds” came last, recorded on June 30, 1970, at Sound City Studios.

Young had attempted the song multiple times over two years.

An August 1969 electric version with vibes accidentally appeared on the “Only Love Can Break Your Heart” B-side.

Young also recorded an acoustic duet with Graham Nash.

The final album version featured Young on solo piano with Crazy Horse on vocals.

This version captured the song’s melancholic bird imagery perfectly.

Musicians & Personnel: After the Gold Rush’s Unlikely Cast

After the gold rush assembled an eclectic mix of musicians from Young’s two primary groups.

The roster blended Crazy Horse members with CSNY collaborators.

Additionally, Young introduced a teenage musical prodigy who couldn’t actually play his assigned instrument.

This unconventional approach created tensions but yielded remarkable results.

The roster blended Crazy Horse members with CSNY collaborators.

Additionally, Young introduced a teenage musical prodigy who couldn’t actually play his assigned instrument.

This unconventional approach created tensions but yielded remarkable results.

Core Musicians

Neil Young handled guitar, piano, harmonica, vibes, and lead vocals throughout.

Danny Whitten contributed guitar and vocals from Crazy Horse.

His deteriorating health limited his contributions but his presence elevated the album.

Ralph Molina played drums and vocals on every track except two.

Billy Talbot played bass on the Sunset Sound recordings.

Greg Reeves, CSNY’s bassist, appeared on the Topanga sessions.

Jack Nitzsche provided piano on “When You Dance I Can Really Love.”

Stephen Stills sang backing vocals, though Young later replaced most with Whitten’s parts.

Bill Peterson played flugelhorn on “After the Gold Rush” and “Till the Morning Comes.”

Danny Whitten contributed guitar and vocals from Crazy Horse.

His deteriorating health limited his contributions but his presence elevated the album.

Ralph Molina played drums and vocals on every track except two.

Billy Talbot played bass on the Sunset Sound recordings.

Greg Reeves, CSNY’s bassist, appeared on the Topanga sessions.

Jack Nitzsche provided piano on “When You Dance I Can Really Love.”

Stephen Stills sang backing vocals, though Young later replaced most with Whitten’s parts.

Bill Peterson played flugelhorn on “After the Gold Rush” and “Till the Morning Comes.”

The Nils Lofgren Story: Piano by Instinct

Nils Lofgren’s participation represents after the gold rush’s most unconventional decision.

Young met the 18-year-old guitarist at Washington D.C.’s Cellar Door club.

Lofgren led the band Grin and impressed Young with his musical intuition.

Young invited him to play piano on the album.

Only one problem existed: Lofgren had never played piano professionally.

“I was back East visiting my folks and when I got back to Topanga I gave Neil and David the bad news,” Lofgren explained.

“I wasn’t a professional pianist.”

Producer David Briggs and Young remained undeterred.

“You’ve been playing classical accordion and winning contests for 10 years,” they told him.

“We just need some simple parts.”

“You’ll figure it out.”

Despite his accordion background, Lofgren felt nervous about the challenge.

He practiced 24/7 at John Locke’s house up the road.

Locke, from the band Spirit, allowed Lofgren to use his piano constantly.

The gamble paid off spectacularly.

Lofgren’s piano work on “Only Love Can Break Your Heart” became iconic.

His contributions on “Tell Me Why,” “Southern Man,” and “Don’t Let It Bring You Down” defined the album’s sound.

Young’s instinct to hire an untrained pianist created the album’s characteristic hesitancy and vulnerability.

A professional might have played with more polish but less emotional truth.

Lofgren later joined Bruce Springsteen’s E Street Band and enjoyed a successful solo career.

Young met the 18-year-old guitarist at Washington D.C.’s Cellar Door club.

Lofgren led the band Grin and impressed Young with his musical intuition.

Young invited him to play piano on the album.

Only one problem existed: Lofgren had never played piano professionally.

“I was back East visiting my folks and when I got back to Topanga I gave Neil and David the bad news,” Lofgren explained.

“I wasn’t a professional pianist.”

Producer David Briggs and Young remained undeterred.

“You’ve been playing classical accordion and winning contests for 10 years,” they told him.

“We just need some simple parts.”

“You’ll figure it out.”

Despite his accordion background, Lofgren felt nervous about the challenge.

He practiced 24/7 at John Locke’s house up the road.

Locke, from the band Spirit, allowed Lofgren to use his piano constantly.

The gamble paid off spectacularly.

Lofgren’s piano work on “Only Love Can Break Your Heart” became iconic.

His contributions on “Tell Me Why,” “Southern Man,” and “Don’t Let It Bring You Down” defined the album’s sound.

Young’s instinct to hire an untrained pianist created the album’s characteristic hesitancy and vulnerability.

A professional might have played with more polish but less emotional truth.

Lofgren later joined Bruce Springsteen’s E Street Band and enjoyed a successful solo career.

The CSNY-Crazy Horse Tension

Biographer Jimmy McDonough asserted Young intentionally mixed musicians from both camps.

Members of Crazy Horse appeared alongside CSNY collaborators.

This strategy frustrated some CSNY members who couldn’t understand Young’s loyalty to Crazy Horse.

“What the fuck do you need Crazy Horse for?” they wondered.

Young maintained both musical relationships despite the friction.

“CSN were fulfilled with what they were doing, and I guess they couldn’t understand why I wasn’t,” Young explained.

“But I had already had this other thing going before and I wasn’t gonna give it up.”

“I had twice as many possibilities as the other guys.”

This dual identity allowed Young greater creative freedom than his bandmates enjoyed.

After the gold rush proved Young didn’t need to choose between commercial polish and raw authenticity.

He could inhabit both worlds simultaneously.

Members of Crazy Horse appeared alongside CSNY collaborators.

This strategy frustrated some CSNY members who couldn’t understand Young’s loyalty to Crazy Horse.

“What the fuck do you need Crazy Horse for?” they wondered.

Young maintained both musical relationships despite the friction.

“CSN were fulfilled with what they were doing, and I guess they couldn’t understand why I wasn’t,” Young explained.

“But I had already had this other thing going before and I wasn’t gonna give it up.”

“I had twice as many possibilities as the other guys.”

This dual identity allowed Young greater creative freedom than his bandmates enjoyed.

After the gold rush proved Young didn’t need to choose between commercial polish and raw authenticity.

He could inhabit both worlds simultaneously.

Track-by-Track Analysis: After the Gold Rush Song by Song

After the gold rush contains eleven tracks spanning 36 minutes.

The album balances acoustic introspection with electric intensity.

Young’s songwriting reached new heights of emotional complexity and lyrical ambiguity.

Several songs feature cryptic lyrics Young himself later admitted he didn’t understand.

The album balances acoustic introspection with electric intensity.

Young’s songwriting reached new heights of emotional complexity and lyrical ambiguity.

Several songs feature cryptic lyrics Young himself later admitted he didn’t understand.

Side One Analysis

“Tell Me Why” (2:45) opens with immediate impact.

Young’s falsetto asks profound questions about compromise and self-worth.

“Tell me why / Is it hard to make arrangements with yourself / When you’re old enough to repay / But young enough to sell?”

Young later admitted the lyrics mystified him.

“I don’t understand it,” he told Spin in 1988.

“It sounds like gibberish to me.”

Nevertheless, the song’s emotional resonance transcends logical interpretation.

Lofgren and Molina provide vocal harmonies that enhance the plaintive quality.

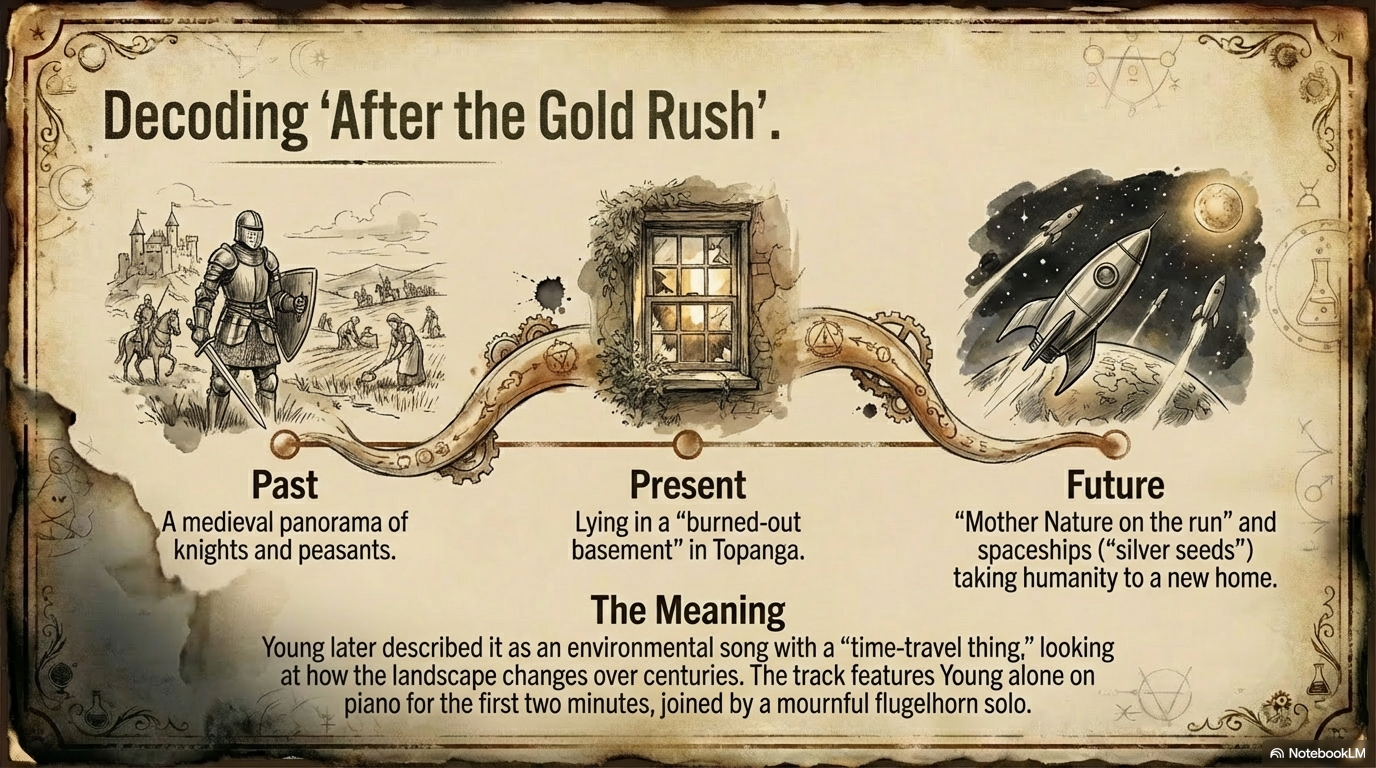

“After the Gold Rush” (3:45) serves as the album’s centerpiece and environmental statement.

Young plays solo piano accompanied only by Bill Peterson’s flugelhorn.

The lyrics depict a dream sequence moving through time.

Medieval pageantry gives way to apocalyptic disaster.

Survivors flee Earth in spacecraft seeking new worlds.

“Look at Mother Nature on the run in the 1970s” became the song’s most quoted line.

Young updates it to current decades when performing live.

The song’s meaning remained unclear even to its creator.

Dolly Parton later asked Young what the song meant.

“He said, ‘I have no idea,'” Parton recalled.

Young eventually described it as an environmental song with time-travel themes.

“Only Love Can Break Your Heart” (3:05) ranks among Young’s most covered compositions.

He wrote it for Graham Nash following Nash’s breakup with Joni Mitchell.

“Neil came to me and said he’d written a song for me, because he knew exactly how I felt,” Nash explained.

Lofgren’s piano provides the foundation for Young’s vulnerable vocal.

Danny Whitten’s backing vocals add depth to the chorus.

The song reached number 33 on the Billboard Hot 100.

“Southern Man” (5:41) addresses slavery and segregation with unflinching directness.

“I saw cotton and I saw black, tall white mansions and little shacks,” Young sings.

“Southern Man, when will you pay them back?”

The song sparked controversy and inspired Lynyrd Skynyrd’s “Sweet Home Alabama” response.

Young wrote it during conflict with his wife Susan Acevedo.

“‘Southern Man’ was an angry song,” Young admitted.

Lofgren’s piano builds intensity throughout the extended arrangement.

The guitar solo showcases Young’s trademark raw, emotional playing style.

Despite the regional controversy, Young and Lynyrd Skynyrd maintained mutual respect.

Ronnie Van Zant wore a Neil Young t-shirt on stage.

“Till the Morning Comes” (1:17) provides brief respite.

Stephen Stills appears on backing vocals alongside the regular cast.

The country-tinged fragment showcases Young’s melodic gift compressed into miniature form.

“Oh, Lonesome Me” (3:47) closes side one with Young’s radical reinterpretation.

Don Gibson’s 1957 country hit transforms into stark folk meditation.

Young’s harmonica makes its first appearance on his recordings.

The arrangement strips away all commercial gloss.

What remains feels timeless and deeply personal.

Young’s falsetto asks profound questions about compromise and self-worth.

“Tell me why / Is it hard to make arrangements with yourself / When you’re old enough to repay / But young enough to sell?”

Young later admitted the lyrics mystified him.

“I don’t understand it,” he told Spin in 1988.

“It sounds like gibberish to me.”

Nevertheless, the song’s emotional resonance transcends logical interpretation.

Lofgren and Molina provide vocal harmonies that enhance the plaintive quality.

“After the Gold Rush” (3:45) serves as the album’s centerpiece and environmental statement.

Young plays solo piano accompanied only by Bill Peterson’s flugelhorn.

The lyrics depict a dream sequence moving through time.

Medieval pageantry gives way to apocalyptic disaster.

Survivors flee Earth in spacecraft seeking new worlds.

“Look at Mother Nature on the run in the 1970s” became the song’s most quoted line.

Young updates it to current decades when performing live.

The song’s meaning remained unclear even to its creator.

Dolly Parton later asked Young what the song meant.

“He said, ‘I have no idea,'” Parton recalled.

Young eventually described it as an environmental song with time-travel themes.

“Only Love Can Break Your Heart” (3:05) ranks among Young’s most covered compositions.

He wrote it for Graham Nash following Nash’s breakup with Joni Mitchell.

“Neil came to me and said he’d written a song for me, because he knew exactly how I felt,” Nash explained.

Lofgren’s piano provides the foundation for Young’s vulnerable vocal.

Danny Whitten’s backing vocals add depth to the chorus.

The song reached number 33 on the Billboard Hot 100.

“Southern Man” (5:41) addresses slavery and segregation with unflinching directness.

“I saw cotton and I saw black, tall white mansions and little shacks,” Young sings.

“Southern Man, when will you pay them back?”

The song sparked controversy and inspired Lynyrd Skynyrd’s “Sweet Home Alabama” response.

Young wrote it during conflict with his wife Susan Acevedo.

“‘Southern Man’ was an angry song,” Young admitted.

Lofgren’s piano builds intensity throughout the extended arrangement.

The guitar solo showcases Young’s trademark raw, emotional playing style.

Despite the regional controversy, Young and Lynyrd Skynyrd maintained mutual respect.

Ronnie Van Zant wore a Neil Young t-shirt on stage.

“Till the Morning Comes” (1:17) provides brief respite.

Stephen Stills appears on backing vocals alongside the regular cast.

The country-tinged fragment showcases Young’s melodic gift compressed into miniature form.

“Oh, Lonesome Me” (3:47) closes side one with Young’s radical reinterpretation.

Don Gibson’s 1957 country hit transforms into stark folk meditation.

Young’s harmonica makes its first appearance on his recordings.

The arrangement strips away all commercial gloss.

What remains feels timeless and deeply personal.

Side Two Analysis

“Don’t Let It Bring You Down” (2:56) explores depression and resilience.

Young wrote it during his first transatlantic trip while touring with CSNY.

The lyrics acknowledge how dark moods can suddenly lift through human connection.

“Every once in awhile something could happen that would get me really depressed,” Young explained.

“Then I would run into somebody and forget about it.”

Lofgren’s piano work perfectly captures the song’s melancholic beauty.

“Birds” (2:34) uses avian imagery as breakup metaphor.

Young attempted recording the song multiple times over two years.

An electric version with vibes accidentally became a B-side.

He also tried an acoustic duet with Graham Nash.

The final solo piano version with Crazy Horse vocals captured the intended intimacy.

“When You Dance I Can Really Love” (3:44) erupts with funky energy.

The only track featuring the complete original Crazy Horse with Jack Nitzsche.

“Jack’s piano on that track is unreal,” Young enthused.

“We were really soaring!”

Billy Talbot’s bass drives the groove.

Ralph Molina’s drums provide steady propulsion.

Danny Whitten’s rhythm guitar adds texture.

The song reached number 93 on the Billboard Hot 100.

“I Believe in You” (3:24) delivers haunting emotional complexity.

Young described the lyrics as “too deep” to discuss.

“Am I lying to you when I say I believe in you?” he questioned.

The song juxtaposes the hopeful chorus against darker verses.

Young rarely performed it live, perhaps finding it too emotionally raw.

“Cripple Creek Ferry” (1:34) closes the album with brief, enigmatic imagery.

The song directly references the Dean Stockwell screenplay.

Its brevity and playfulness provide light after the preceding intensity.

The album ends without definitive resolution, mirroring life’s ongoing complexities.

Young wrote it during his first transatlantic trip while touring with CSNY.

The lyrics acknowledge how dark moods can suddenly lift through human connection.

“Every once in awhile something could happen that would get me really depressed,” Young explained.

“Then I would run into somebody and forget about it.”

Lofgren’s piano work perfectly captures the song’s melancholic beauty.

“Birds” (2:34) uses avian imagery as breakup metaphor.

Young attempted recording the song multiple times over two years.

An electric version with vibes accidentally became a B-side.

He also tried an acoustic duet with Graham Nash.

The final solo piano version with Crazy Horse vocals captured the intended intimacy.

“When You Dance I Can Really Love” (3:44) erupts with funky energy.

The only track featuring the complete original Crazy Horse with Jack Nitzsche.

“Jack’s piano on that track is unreal,” Young enthused.

“We were really soaring!”

Billy Talbot’s bass drives the groove.

Ralph Molina’s drums provide steady propulsion.

Danny Whitten’s rhythm guitar adds texture.

The song reached number 93 on the Billboard Hot 100.

“I Believe in You” (3:24) delivers haunting emotional complexity.

Young described the lyrics as “too deep” to discuss.

“Am I lying to you when I say I believe in you?” he questioned.

The song juxtaposes the hopeful chorus against darker verses.

Young rarely performed it live, perhaps finding it too emotionally raw.

“Cripple Creek Ferry” (1:34) closes the album with brief, enigmatic imagery.

The song directly references the Dean Stockwell screenplay.

Its brevity and playfulness provide light after the preceding intensity.

The album ends without definitive resolution, mirroring life’s ongoing complexities.

Singles & Chart Performance: Commercial Reception

Three singles emerged from after the gold rush with varying commercial success.

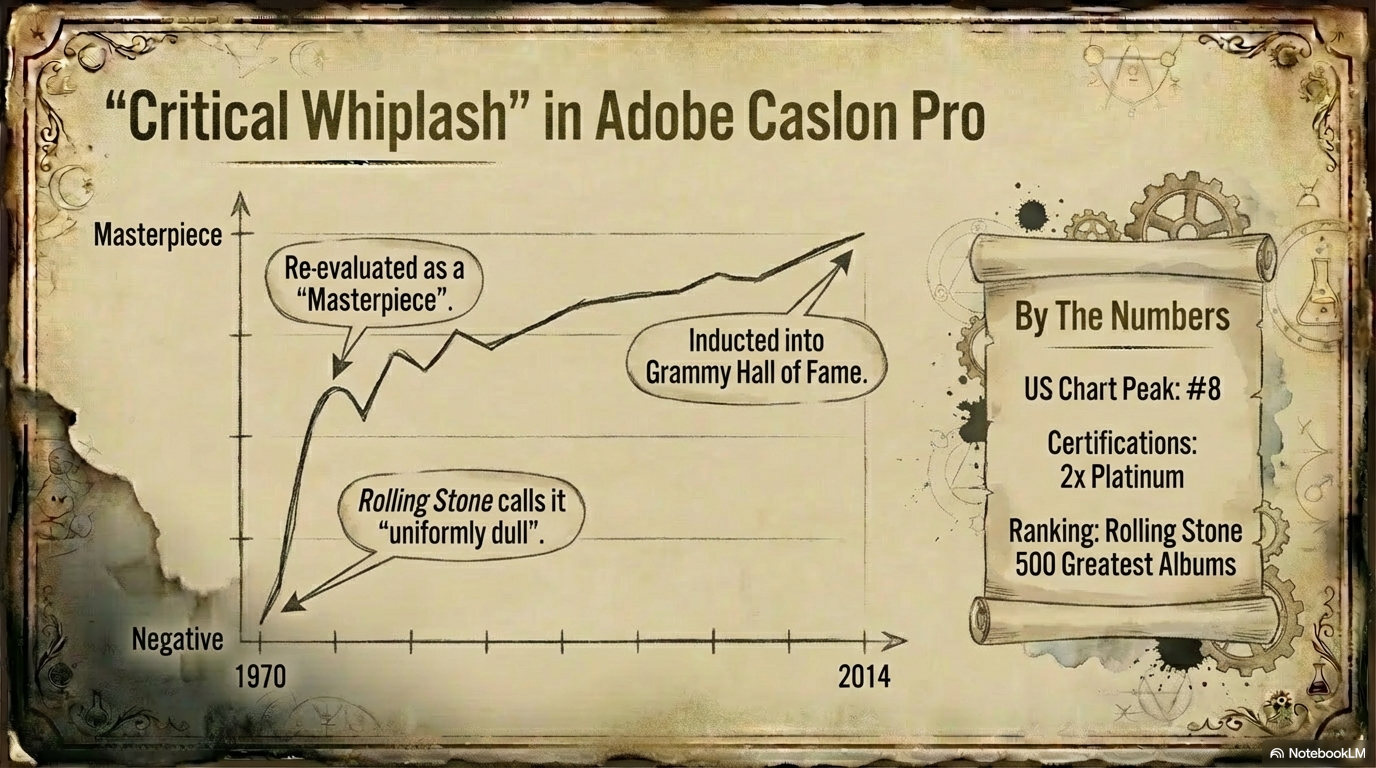

The album itself peaked at number eight on Billboard’s Top Pop Albums chart.

This represented Young’s highest chart position for a solo album to that point.

The album entered the chart on September 19, 1970, the same day as its release.

The album itself peaked at number eight on Billboard’s Top Pop Albums chart.

This represented Young’s highest chart position for a solo album to that point.

The album entered the chart on September 19, 1970, the same day as its release.

Single Releases and Radio Success

“Oh Lonesome Me” appeared first as a single in February 1970.

Reprise released it ahead of the album alongside “I’ve Been Waiting for You.”

The advance single generated modest interest but failed to chart.

“Only Love Can Break Your Heart” arrived October 19, 1970, with “Birds” as the B-side.

The single entered the Billboard Hot 100 on October 24, 1970.

It peaked at number 33, becoming the album’s biggest hit.

Interestingly, an electric outtake of “Birds” with vibes accidentally appeared on early pressings.

This version lacked the second verse Young forgot during recording.

The error became a collector’s item once corrected.

“When You Dance I Can Really Love” followed in March 1971.

“Sugar Mountain” served as the B-side.

The funky track reached number 93 on the Billboard Hot 100.

While not a major hit, it received significant FM radio airplay.

Progressive radio stations particularly embraced the song’s groove.

Reprise released it ahead of the album alongside “I’ve Been Waiting for You.”

The advance single generated modest interest but failed to chart.

“Only Love Can Break Your Heart” arrived October 19, 1970, with “Birds” as the B-side.

The single entered the Billboard Hot 100 on October 24, 1970.

It peaked at number 33, becoming the album’s biggest hit.

Interestingly, an electric outtake of “Birds” with vibes accidentally appeared on early pressings.

This version lacked the second verse Young forgot during recording.

The error became a collector’s item once corrected.

“When You Dance I Can Really Love” followed in March 1971.

“Sugar Mountain” served as the B-side.

The funky track reached number 93 on the Billboard Hot 100.

While not a major hit, it received significant FM radio airplay.

Progressive radio stations particularly embraced the song’s groove.

Album Sales and Certifications

After the gold rush achieved double platinum certification in both the United States and United Kingdom.

This represents sales exceeding two million copies in each territory.

The album sold consistently throughout the 1970s rather than achieving immediate blockbuster status.

Word of mouth and critical reassessment drove sustained sales over years.

The album charted in multiple countries beyond the United States.

Australia, Canada, Norway, and several European nations embraced the album.

The album’s longevity outpaced many contemporary releases that achieved higher initial chart positions.

After the gold rush never left the public consciousness, appearing on countless greatest albums lists.

This represents sales exceeding two million copies in each territory.

The album sold consistently throughout the 1970s rather than achieving immediate blockbuster status.

Word of mouth and critical reassessment drove sustained sales over years.

The album charted in multiple countries beyond the United States.

Australia, Canada, Norway, and several European nations embraced the album.

The album’s longevity outpaced many contemporary releases that achieved higher initial chart positions.

After the gold rush never left the public consciousness, appearing on countless greatest albums lists.

Cover Versions and Cultural Impact

“After the Gold Rush” became one of Young’s most covered songs.

The vocal group Prelude scored an international hit with an a cappella version in 1974.

Their interpretation reached number 22 on the U.S. Hot 100.

In the UK, it peaked within the Top 40 twice: 1974 and again in 1982.

Canada embraced Prelude’s version, where it reached number five.

Dolly Parton, Emmylou Harris, and Linda Ronstadt recorded it for their 1999 album Trio II.

They changed “getting high” to “I could cry” at the singers’ request.

Their version won the Grammy Award for Best Country Collaboration with Vocals in 2000.

Numerous other artists recorded versions spanning multiple genres.

The song transcended its folk-rock origins to become a standard.

“Only Love Can Break Your Heart” inspired countless covers across five decades.

Everyone from punk bands to country artists reinterpreted the classic.

The song’s simple chord structure and emotional directness made it endlessly adaptable.

The vocal group Prelude scored an international hit with an a cappella version in 1974.

Their interpretation reached number 22 on the U.S. Hot 100.

In the UK, it peaked within the Top 40 twice: 1974 and again in 1982.

Canada embraced Prelude’s version, where it reached number five.

Dolly Parton, Emmylou Harris, and Linda Ronstadt recorded it for their 1999 album Trio II.

They changed “getting high” to “I could cry” at the singers’ request.

Their version won the Grammy Award for Best Country Collaboration with Vocals in 2000.

Numerous other artists recorded versions spanning multiple genres.

The song transcended its folk-rock origins to become a standard.

“Only Love Can Break Your Heart” inspired countless covers across five decades.

Everyone from punk bands to country artists reinterpreted the classic.

The song’s simple chord structure and emotional directness made it endlessly adaptable.

Critical Reception: From “Half-Baked” to Masterpiece

After the gold rush received one of rock criticism’s most notorious initial assessments.

Rolling Stone assigned the review to Langdon Winner.

His October 15, 1970 review remains infamous for its harsh dismissal.

“Neil Young devotees will probably spend the next few weeks trying desperately to convince themselves that After The Gold Rush is good music,” Winner wrote.

“But they’ll be kidding themselves.”

Rolling Stone assigned the review to Langdon Winner.

His October 15, 1970 review remains infamous for its harsh dismissal.

“Neil Young devotees will probably spend the next few weeks trying desperately to convince themselves that After The Gold Rush is good music,” Winner wrote.

“But they’ll be kidding themselves.”

The Rolling Stone Disaster

Winner’s review criticized nearly every aspect of the album.

“Despite the fact that the album contains some potentially first rate material, none of the songs here rise above the uniformly dull surface,” he complained.

He described the ensemble playing as “sloppy and disconnected.”

Winner compared Young’s vocals to “Mrs. Miller moaning and wheezing her way through ‘I’m A Lonely Little Petunia In An Onion Patch.'”

The review concluded: “This record picks up where Deja Vu leaves off.”

This final line referenced Winner’s previous negative review of CSNY’s album.

Rolling Stone readers who’d written in outrage about that review received Winner’s dismissive acknowledgment.

The review stands as one of rock criticism’s most spectacular misjudgments.

Within five years, Rolling Stone would call after the gold rush a “masterpiece.”

By 1975, Dave Marsh’s review of Tonight’s the Night referenced the album reverently.

The magazine included it on their 500 Greatest Albums of All Time lists.

It ranked 71st in 2003, 74th in 2012, and 90th in 2020.

“Despite the fact that the album contains some potentially first rate material, none of the songs here rise above the uniformly dull surface,” he complained.

He described the ensemble playing as “sloppy and disconnected.”

Winner compared Young’s vocals to “Mrs. Miller moaning and wheezing her way through ‘I’m A Lonely Little Petunia In An Onion Patch.'”

The review concluded: “This record picks up where Deja Vu leaves off.”

This final line referenced Winner’s previous negative review of CSNY’s album.

Rolling Stone readers who’d written in outrage about that review received Winner’s dismissive acknowledgment.

The review stands as one of rock criticism’s most spectacular misjudgments.

Within five years, Rolling Stone would call after the gold rush a “masterpiece.”

By 1975, Dave Marsh’s review of Tonight’s the Night referenced the album reverently.

The magazine included it on their 500 Greatest Albums of All Time lists.

It ranked 71st in 2003, 74th in 2012, and 90th in 2020.

Positive Contemporary Voices

Not every critic missed the album’s brilliance initially.

Village Voice critic Robert Christgau immediately recognized the album’s quality.

His contemporaneous review praised Young’s unique achievement.

“While David Crosby yowls about assassinations, Young divulges darker agonies without even bothering to make them explicit,” Christgau wrote.

“Here the gaunt pain of Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere fills out a little.”

“The voice softer, the jangling guitar muted behind a piano.”

Christgau identified the album as “a real rarity: pleasant and hard at the same time.”

In his 1998 book Grown Up All Wrong, Christgau named after the gold rush his favorite Neil Young album.

This assessment proved more prescient than Winner’s dismissal.

Many fans immediately embraced the album despite critical skepticism.

The disconnect between professional reviewers and audiences became apparent quickly.

Village Voice critic Robert Christgau immediately recognized the album’s quality.

His contemporaneous review praised Young’s unique achievement.

“While David Crosby yowls about assassinations, Young divulges darker agonies without even bothering to make them explicit,” Christgau wrote.

“Here the gaunt pain of Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere fills out a little.”

“The voice softer, the jangling guitar muted behind a piano.”

Christgau identified the album as “a real rarity: pleasant and hard at the same time.”

In his 1998 book Grown Up All Wrong, Christgau named after the gold rush his favorite Neil Young album.

This assessment proved more prescient than Winner’s dismissal.

Many fans immediately embraced the album despite critical skepticism.

The disconnect between professional reviewers and audiences became apparent quickly.

Legacy and Accolades

After the gold rush now appears on virtually every significant greatest albums list.

Time magazine included it in their All-Time 100 Albums in 2006.

Pitchfork ranked it 99th on their Top 100 Albums of the 1970s in 2004.

Bob Mersereau’s 2007 book The Top 100 Canadian Albums placed it third.

Only Young’s own Harvest ranked higher in that specific survey.

Chart magazine readers voted it fifth among best Canadian albums in 2005.

New Musical Express named it the 56th greatest album of all time in 2013.

Blender called it the 86th greatest “American” album in 2002.

The book 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die includes it.

Colin Larkin’s All Time Top 1000 Albums ranked it 62nd in 2000.

Q magazine readers voted it the 89th greatest album of all time in 1998.

The Grammy Hall of Fame inducted the album in 2014.

This honor recognizes recordings of lasting qualitative or historical significance.

The album’s reputation only strengthened with each passing decade.

Critics who initially dismissed it rarely acknowledged their error.

However, their publications’ reassessments speak volumes.

Time magazine included it in their All-Time 100 Albums in 2006.

Pitchfork ranked it 99th on their Top 100 Albums of the 1970s in 2004.

Bob Mersereau’s 2007 book The Top 100 Canadian Albums placed it third.

Only Young’s own Harvest ranked higher in that specific survey.

Chart magazine readers voted it fifth among best Canadian albums in 2005.

New Musical Express named it the 56th greatest album of all time in 2013.

Blender called it the 86th greatest “American” album in 2002.

The book 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die includes it.

Colin Larkin’s All Time Top 1000 Albums ranked it 62nd in 2000.

Q magazine readers voted it the 89th greatest album of all time in 1998.

The Grammy Hall of Fame inducted the album in 2014.

This honor recognizes recordings of lasting qualitative or historical significance.

The album’s reputation only strengthened with each passing decade.

Critics who initially dismissed it rarely acknowledged their error.

However, their publications’ reassessments speak volumes.

Musical Style & Themes: The Sound of Transition

After the gold rush defies simple genre classification.

The album weaves country folk, rock, and singer-songwriter intimacy into a cohesive whole.

Young shifts between acoustic vulnerability and electric intensity within single songs.

This stylistic fluidity became a defining characteristic of his subsequent career.

The album weaves country folk, rock, and singer-songwriter intimacy into a cohesive whole.

Young shifts between acoustic vulnerability and electric intensity within single songs.

This stylistic fluidity became a defining characteristic of his subsequent career.

Instrumental Palette and Arrangements

Piano dominates after the gold rush more than any previous Young album.

Young plays piano on five tracks as the primary instrument.

Nils Lofgren’s piano appears on another four.

Jack Nitzsche contributes piano to one song.

This piano-forward approach distinguished the album from Young’s guitar-driven earlier work.

The acoustic guitar provides foundation for several tracks.

Electric guitar appears sparingly but effectively, particularly on “Southern Man.”

Young introduces harmonica for the first time on “Oh, Lonesome Me.”

Bill Peterson’s flugelhorn adds haunting texture to two songs.

Vibes appear on “I Believe in You,” creating an otherworldly atmosphere.

The sparse arrangements leave significant empty space.

This negative space allows Young’s voice and lyrics room to breathe.

Bass and drums provide unobtrusive support rather than driving the arrangements.

The overall production aesthetic favors intimacy over polish.

David Briggs’ production philosophy emphasized capturing honest performances.

Technical perfection took a back seat to emotional authenticity.

This approach frustrated contemporary reviewers accustomed to slicker production.

However, the raw quality contributed to the album’s timeless appeal.

Young plays piano on five tracks as the primary instrument.

Nils Lofgren’s piano appears on another four.

Jack Nitzsche contributes piano to one song.

This piano-forward approach distinguished the album from Young’s guitar-driven earlier work.

The acoustic guitar provides foundation for several tracks.

Electric guitar appears sparingly but effectively, particularly on “Southern Man.”

Young introduces harmonica for the first time on “Oh, Lonesome Me.”

Bill Peterson’s flugelhorn adds haunting texture to two songs.

Vibes appear on “I Believe in You,” creating an otherworldly atmosphere.

The sparse arrangements leave significant empty space.

This negative space allows Young’s voice and lyrics room to breathe.

Bass and drums provide unobtrusive support rather than driving the arrangements.

The overall production aesthetic favors intimacy over polish.

David Briggs’ production philosophy emphasized capturing honest performances.

Technical perfection took a back seat to emotional authenticity.

This approach frustrated contemporary reviewers accustomed to slicker production.

However, the raw quality contributed to the album’s timeless appeal.

Lyrical Themes and Poetic Ambiguity

Young’s lyrics on after the gold rush embrace ambiguity and mystery.

Environmental concerns thread through multiple songs.

The title track depicts ecological disaster and humanity’s search for new worlds.

“Look at Mother Nature on the run” became an environmental anthem.

Social justice emerges explicitly on “Southern Man.”

The song confronts racism without apology or compromise.

Personal relationships receive tender, vulnerable treatment.

“Only Love Can Break Your Heart” explores romantic fragility.

“I Believe in You” questions the nature of commitment itself.

“Birds” uses metaphor to describe lost love.

Existential loneliness permeates “Don’t Let It Bring You Down.”

The song acknowledges depression while suggesting connection as antidote.

Many lyrics resist clear interpretation.

Young himself admitted not understanding some of his own songs.

This cryptic quality invites listeners to find personal meaning.

Each person discovers their own truth within the songs.

The poetic ambiguity prevents the album from dating.

Specific references remain minimal, allowing universal themes to dominate.

Young captured eternal human experiences rather than temporal concerns.

Environmental concerns thread through multiple songs.

The title track depicts ecological disaster and humanity’s search for new worlds.

“Look at Mother Nature on the run” became an environmental anthem.

Social justice emerges explicitly on “Southern Man.”

The song confronts racism without apology or compromise.

Personal relationships receive tender, vulnerable treatment.

“Only Love Can Break Your Heart” explores romantic fragility.

“I Believe in You” questions the nature of commitment itself.

“Birds” uses metaphor to describe lost love.

Existential loneliness permeates “Don’t Let It Bring You Down.”

The song acknowledges depression while suggesting connection as antidote.

Many lyrics resist clear interpretation.

Young himself admitted not understanding some of his own songs.

This cryptic quality invites listeners to find personal meaning.

Each person discovers their own truth within the songs.

The poetic ambiguity prevents the album from dating.

Specific references remain minimal, allowing universal themes to dominate.

Young captured eternal human experiences rather than temporal concerns.

Vocal Delivery and Emotional Range

Young’s distinctive voice defines after the gold rush’s emotional landscape.

His high tenor and frequent use of falsetto became signature elements.

Some listeners initially found his voice off-putting or unconventional.

Langdon Winner’s “Mrs. Miller” comparison reflected this perspective.

However, Young’s voice perfectly conveyed vulnerability and wounded emotion.

The slight quaver in his delivery communicated authentic feeling.

On “Tell Me Why” and “Only Love Can Break Your Heart,” his falsetto soars.

“Southern Man” showcases his ability to channel anger through his vocals.

The softer moments on “Birds” and “I Believe in You” reveal tender introspection.

Young never aimed for technical perfection in his singing.

He prioritized emotional truth over vocal beauty.

This approach distinguished him from contemporaries focused on virtuosity.

His voice became an instrument of direct emotional transmission.

Listeners either connected deeply or found it jarring.

Few remained neutral about Young’s vocal approach.

The backing vocals from Crazy Horse members added warmth to many tracks.

Danny Whitten’s harmonies particularly enhanced the communal feeling.

The blend of voices created intimacy without professional polish.

His high tenor and frequent use of falsetto became signature elements.

Some listeners initially found his voice off-putting or unconventional.

Langdon Winner’s “Mrs. Miller” comparison reflected this perspective.

However, Young’s voice perfectly conveyed vulnerability and wounded emotion.

The slight quaver in his delivery communicated authentic feeling.

On “Tell Me Why” and “Only Love Can Break Your Heart,” his falsetto soars.

“Southern Man” showcases his ability to channel anger through his vocals.

The softer moments on “Birds” and “I Believe in You” reveal tender introspection.

Young never aimed for technical perfection in his singing.

He prioritized emotional truth over vocal beauty.

This approach distinguished him from contemporaries focused on virtuosity.

His voice became an instrument of direct emotional transmission.

Listeners either connected deeply or found it jarring.

Few remained neutral about Young’s vocal approach.

The backing vocals from Crazy Horse members added warmth to many tracks.

Danny Whitten’s harmonies particularly enhanced the communal feeling.

The blend of voices created intimacy without professional polish.

Album Artwork & Packaging: Solarized Greenwich Village

Art director Gary Burden designed the after the gold rush album cover.

This collaboration marked the beginning of a five-decade creative partnership.

Burden worked on virtually every Neil Young album until his death in 2018.

Young described Burden as one of his closest compadres.

“Gary and I have been working together since that time,” Young wrote.

“He is one of my closest compadres.”

“We are doing our life’s work together.”

This collaboration marked the beginning of a five-decade creative partnership.

Burden worked on virtually every Neil Young album until his death in 2018.

Young described Burden as one of his closest compadres.

“Gary and I have been working together since that time,” Young wrote.

“He is one of my closest compadres.”

“We are doing our life’s work together.”

The Greenwich Village Photograph

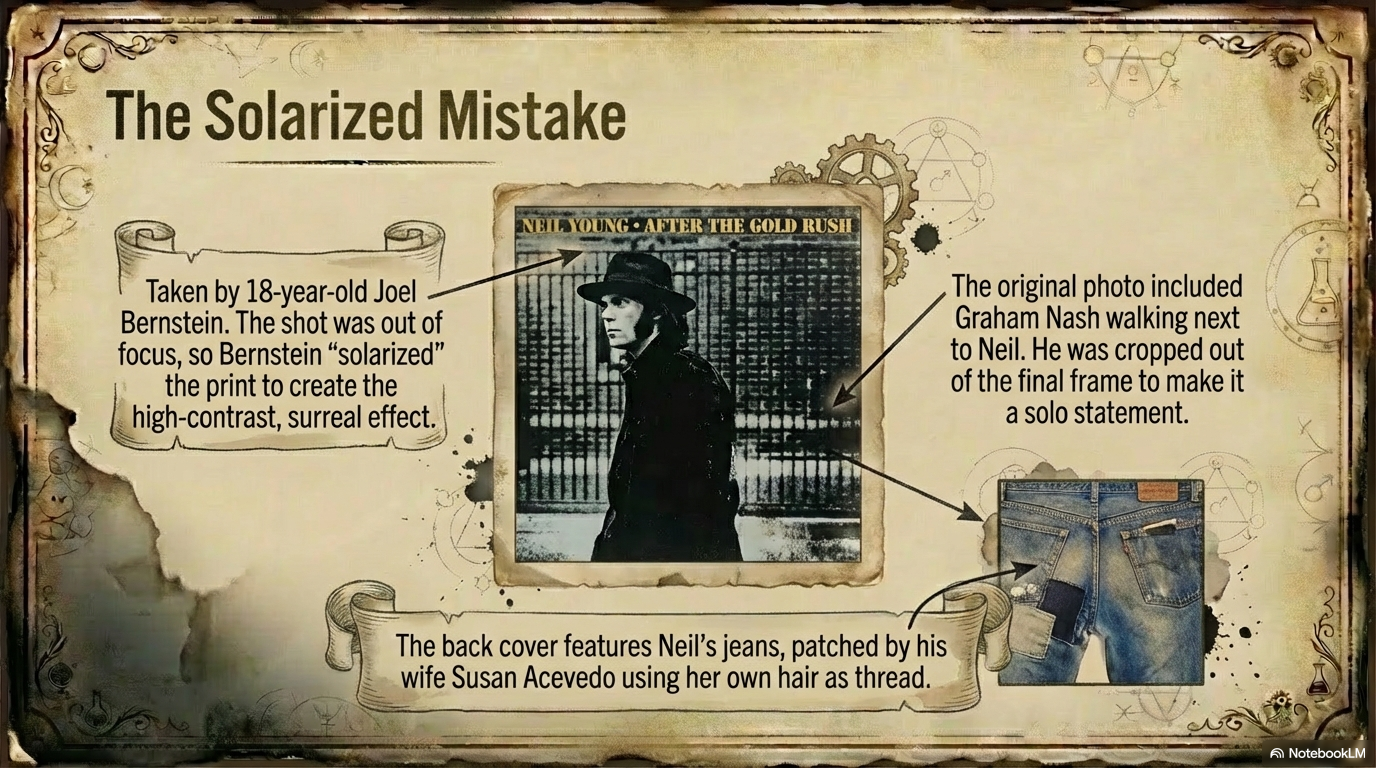

Photographer Joel Bernstein captured the front cover image in early 1970.

Bernstein was only 18 years old at the time.

The photo shows Young walking past an elderly woman at the New York University School of Law.

The location sits in Greenwich Village near Washington Square Park.

Bernstein shot the image during an outdoor photo session.

However, the photograph came out slightly out of focus.

Bernstein decided to solarize the print to mask the soft focus.

This photographic technique reversed tones and created a dreamlike quality.

Young chose this “accidental shot” for the cover to Bernstein’s surprise.

“Shocked” was how Bernstein described his reaction to Young’s choice.

The solarization process gave the image its distinctive, otherworldly appearance.

The effect perfectly matched the album’s themes of transformation and uncertainty.

The original uncropped photo revealed an additional figure.

Graham Nash, Young’s CSNY bandmate, walked beside him.

Burden and Young cropped Nash from the final cover.

This decision emphasized Young’s solo identity separate from CSNY.

The sidewalk location on MacDougal Street became a pilgrimage site for fans.

The specific fence and brick base visible in the photo no longer exist.

NYU replaced them between 1981 and 1987 during underground library construction.

Bernstein was only 18 years old at the time.

The photo shows Young walking past an elderly woman at the New York University School of Law.

The location sits in Greenwich Village near Washington Square Park.

Bernstein shot the image during an outdoor photo session.

However, the photograph came out slightly out of focus.

Bernstein decided to solarize the print to mask the soft focus.

This photographic technique reversed tones and created a dreamlike quality.

Young chose this “accidental shot” for the cover to Bernstein’s surprise.

“Shocked” was how Bernstein described his reaction to Young’s choice.

The solarization process gave the image its distinctive, otherworldly appearance.

The effect perfectly matched the album’s themes of transformation and uncertainty.

The original uncropped photo revealed an additional figure.

Graham Nash, Young’s CSNY bandmate, walked beside him.

Burden and Young cropped Nash from the final cover.

This decision emphasized Young’s solo identity separate from CSNY.

The sidewalk location on MacDougal Street became a pilgrimage site for fans.

The specific fence and brick base visible in the photo no longer exist.

NYU replaced them between 1981 and 1987 during underground library construction.

The Back Cover Patches

The album’s back cover shows the rear view of Young’s patched jeans.

His first wife, Susan Acevedo, created these patches.

She sewed them using strands of her own hair as thread.

“Susan, my first wife, made all those cool patches I wore back in the day,” Young recalled.

“The pants on the back cover of After the Gold Rush were Susan’s work.”

She also made Young a beautiful patchwork vest with a blue velvet back.

After their marriage ended, Young carefully preserved the vest.

“After we broke up, I wanted to keep it carefully tucked away forever,” he wrote.

“It was beautiful.”

“I wanted to always remember her by it.”

The back cover photograph captured a moment of Young’s personal history.

The patches symbolized love, craftsmanship, and the handmade aesthetic of the era.

Susan’s artistic contributions extended beyond these visible items.

She influenced songs and creative decisions throughout their marriage.

The album cover art and packaging reflected Young’s life in totality.

Both personal relationships and artistic choices intertwined throughout the project.

His first wife, Susan Acevedo, created these patches.

She sewed them using strands of her own hair as thread.

“Susan, my first wife, made all those cool patches I wore back in the day,” Young recalled.

“The pants on the back cover of After the Gold Rush were Susan’s work.”

She also made Young a beautiful patchwork vest with a blue velvet back.

After their marriage ended, Young carefully preserved the vest.

“After we broke up, I wanted to keep it carefully tucked away forever,” he wrote.

“It was beautiful.”

“I wanted to always remember her by it.”

The back cover photograph captured a moment of Young’s personal history.

The patches symbolized love, craftsmanship, and the handmade aesthetic of the era.

Susan’s artistic contributions extended beyond these visible items.

She influenced songs and creative decisions throughout their marriage.

The album cover art and packaging reflected Young’s life in totality.

Both personal relationships and artistic choices intertwined throughout the project.

Reissues and Anniversary Editions

Reprise originally released after the gold rush on vinyl in September 1970.

The first CD release arrived in 1986 during the format’s early adoption period.

A remastered HDCD version appeared on July 14, 2009.

This release formed part of the Neil Young Archives Original Release Series.

The remaster improved sound quality while maintaining the album’s original character.

The 50th anniversary brought special editions in 2020 and 2021.

A CD version released December 11, 2020, featured enhanced cover art.

The original image received a “50” designation below the title.

A limited edition vinyl box set followed on March 19, 2021.

The box set included two versions of the outtake “Wonderin’.”

One version came on CD as bonus tracks.

Another appeared on a 7-inch 45rpm single with picture sleeve.

The Topanga recording dated from March 1970.

The Sunset Sound version remained previously unreleased since August 1969 recording.

Digital high-resolution files became available through Neil Young Archives website.

A 3:36 outtake of “Birds” from Sunset Sound sessions joined the archive.

These anniversary editions allowed new generations to discover the album.

They also provided longtime fans with archival treasures.

The first CD release arrived in 1986 during the format’s early adoption period.

A remastered HDCD version appeared on July 14, 2009.

This release formed part of the Neil Young Archives Original Release Series.

The remaster improved sound quality while maintaining the album’s original character.

The 50th anniversary brought special editions in 2020 and 2021.

A CD version released December 11, 2020, featured enhanced cover art.

The original image received a “50” designation below the title.

A limited edition vinyl box set followed on March 19, 2021.

The box set included two versions of the outtake “Wonderin’.”

One version came on CD as bonus tracks.

Another appeared on a 7-inch 45rpm single with picture sleeve.

The Topanga recording dated from March 1970.

The Sunset Sound version remained previously unreleased since August 1969 recording.

Digital high-resolution files became available through Neil Young Archives website.

A 3:36 outtake of “Birds” from Sunset Sound sessions joined the archive.

These anniversary editions allowed new generations to discover the album.

They also provided longtime fans with archival treasures.

Legacy & Influence: After the Gold Rush’s Enduring Impact

After the gold rush established the artistic template Young would follow for five decades.

The album proved commercial success didn’t require compromise or polish.

Authenticity and emotional honesty could coexist with chart positions and sales.

This lesson influenced countless artists across multiple generations.

The album proved commercial success didn’t require compromise or polish.

Authenticity and emotional honesty could coexist with chart positions and sales.

This lesson influenced countless artists across multiple generations.

Defining the Singer-Songwriter Aesthetic

After the gold rush helped define the early 1970s singer-songwriter movement.

Young’s confessional approach influenced James Taylor, Jackson Browne, and countless others.

The stripped-down production showed that expensive studios weren’t necessary.

A basement could yield results as powerful as professional facilities.

This DIY ethic resonated through punk, indie rock, and alternative music.

Young’s willingness to embrace imperfection gave others permission to do likewise.

The album’s success proved audiences valued emotional truth over technical precision.

Musicians learned they could release raw, vulnerable work without apologizing.

The alternative to slick, commercial production became a viable artistic choice.

Later artists like Elliott Smith, Bright Eyes, and Bon Iver followed this path.

They recorded intimate albums emphasizing emotion over production values.

Young’s influence appears throughout the indie folk and alternative country movements.

The album demonstrated that a piano ballad could sit beside a fierce rock track.

Genre boundaries became less relevant than emotional cohesion.

This cross-pollination approach characterized much progressive 1970s rock music.

Artists learned to trust their instincts rather than commercial expectations.

Young’s confessional approach influenced James Taylor, Jackson Browne, and countless others.

The stripped-down production showed that expensive studios weren’t necessary.

A basement could yield results as powerful as professional facilities.

This DIY ethic resonated through punk, indie rock, and alternative music.

Young’s willingness to embrace imperfection gave others permission to do likewise.

The album’s success proved audiences valued emotional truth over technical precision.

Musicians learned they could release raw, vulnerable work without apologizing.

The alternative to slick, commercial production became a viable artistic choice.

Later artists like Elliott Smith, Bright Eyes, and Bon Iver followed this path.

They recorded intimate albums emphasizing emotion over production values.

Young’s influence appears throughout the indie folk and alternative country movements.

The album demonstrated that a piano ballad could sit beside a fierce rock track.

Genre boundaries became less relevant than emotional cohesion.

This cross-pollination approach characterized much progressive 1970s rock music.

Artists learned to trust their instincts rather than commercial expectations.

Environmental and Social Consciousness

The album’s environmental themes proved remarkably prescient.

“After the Gold Rush” addressed ecological disaster in 1970.

Climate change concerns were barely emerging in mainstream consciousness.

Young’s vision of Mother Nature “on the run” anticipated decades of environmental activism.

The song became an anthem for ecological movements.

“Southern Man” showed rock music could address racism directly.

The song didn’t soften its message for commercial considerations.

Young confronted segregation and slavery’s legacy without apology.

This directness inspired subsequent generations of politically engaged musicians.

Bruce Springsteen, Rage Against the Machine, and others followed Young’s example.

They demonstrated that commercial success and social consciousness could coexist.

Artists learned they could address serious issues without abandoning their audience.

The Lynyrd Skynyrd response to “Southern Man” sparked important conversations.

Even disagreement advanced dialogue about regional identity and racial justice.

Young proved that controversy wouldn’t destroy a career.

Speaking uncomfortable truths might actually deepen an artist’s connection with audiences.

This lesson encouraged artists to take risks with challenging material.

“After the Gold Rush” addressed ecological disaster in 1970.

Climate change concerns were barely emerging in mainstream consciousness.

Young’s vision of Mother Nature “on the run” anticipated decades of environmental activism.

The song became an anthem for ecological movements.

“Southern Man” showed rock music could address racism directly.

The song didn’t soften its message for commercial considerations.

Young confronted segregation and slavery’s legacy without apology.

This directness inspired subsequent generations of politically engaged musicians.

Bruce Springsteen, Rage Against the Machine, and others followed Young’s example.

They demonstrated that commercial success and social consciousness could coexist.

Artists learned they could address serious issues without abandoning their audience.

The Lynyrd Skynyrd response to “Southern Man” sparked important conversations.

Even disagreement advanced dialogue about regional identity and racial justice.

Young proved that controversy wouldn’t destroy a career.

Speaking uncomfortable truths might actually deepen an artist’s connection with audiences.

This lesson encouraged artists to take risks with challenging material.

Career Impact and Artistic Freedom

After the gold rush established Young’s commercial viability as a solo artist.

The album’s success gave him leverage to pursue diverse creative directions.

He could record folk, rock, country, or experimental electronic music.

Audiences trusted Young to deliver quality regardless of style.

This freedom distinguished Young from peers trapped in successful formulas.

The album preceded Harvest, Young’s biggest commercial success.

However, after the gold rush proved more influential artistically.

Its rawness and emotional honesty aged better than Harvest’s polish.

Many consider after the gold rush Young’s most consistent album.

It lacks the self-conscious ambition of later concept albums.

The album simply presents eleven strong songs unified by mood and sensibility.

This deceptive simplicity makes it endlessly listenable.

Young’s willingness to follow his muse rather than repeat successes began here.

The pattern of releasing commercially successful albums followed by difficult experimental work started with after the gold rush.

Young refused to become predictable or safe.

This artistic restlessness kept his career vital across six decades.

The album taught Young he could trust his instincts.

Commercial considerations mattered less than artistic truth.

This philosophy sustained one of rock’s longest and most productive careers.

The album’s success gave him leverage to pursue diverse creative directions.

He could record folk, rock, country, or experimental electronic music.

Audiences trusted Young to deliver quality regardless of style.

This freedom distinguished Young from peers trapped in successful formulas.

The album preceded Harvest, Young’s biggest commercial success.

However, after the gold rush proved more influential artistically.

Its rawness and emotional honesty aged better than Harvest’s polish.

Many consider after the gold rush Young’s most consistent album.

It lacks the self-conscious ambition of later concept albums.

The album simply presents eleven strong songs unified by mood and sensibility.

This deceptive simplicity makes it endlessly listenable.

Young’s willingness to follow his muse rather than repeat successes began here.

The pattern of releasing commercially successful albums followed by difficult experimental work started with after the gold rush.

Young refused to become predictable or safe.

This artistic restlessness kept his career vital across six decades.

The album taught Young he could trust his instincts.

Commercial considerations mattered less than artistic truth.

This philosophy sustained one of rock’s longest and most productive careers.

Place in Young’s Discography

After the gold rush occupies a pivotal position in Neil Young’s vast catalog.

It sits between the raw Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere and the polished Harvest.

The album balances both approaches, pointing toward Young’s future career.

Many Young fans consider it his most essential album.

It introduces new listeners to his strengths without overwhelming them.

The album showcases Young’s songwriting, voice, and artistic vision in concentrated form.

Unlike later, more sprawling efforts, after the gold rush maintains tight focus.

Eleven songs in 36 minutes leave listeners wanting more rather than feeling exhausted.

The album regularly appears at the top of “Best of Neil Young” lists.

Fans debate whether after the gold rush or other albums represent his peak.

However, few question its importance to his artistic development.

The album demonstrated Young’s range while establishing his core identity.

It proved he could sustain a complete album vision rather than just individual songs.

This album confidence carried through decades of subsequent releases.

Young never made another album exactly like after the gold rush.

However, its spirit appears throughout his best work.

The balance of vulnerability and strength, intimacy and power, became his signature.

It sits between the raw Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere and the polished Harvest.

The album balances both approaches, pointing toward Young’s future career.

Many Young fans consider it his most essential album.

It introduces new listeners to his strengths without overwhelming them.

The album showcases Young’s songwriting, voice, and artistic vision in concentrated form.

Unlike later, more sprawling efforts, after the gold rush maintains tight focus.

Eleven songs in 36 minutes leave listeners wanting more rather than feeling exhausted.

The album regularly appears at the top of “Best of Neil Young” lists.

Fans debate whether after the gold rush or other albums represent his peak.

However, few question its importance to his artistic development.

The album demonstrated Young’s range while establishing his core identity.

It proved he could sustain a complete album vision rather than just individual songs.

This album confidence carried through decades of subsequent releases.

Young never made another album exactly like after the gold rush.

However, its spirit appears throughout his best work.

The balance of vulnerability and strength, intimacy and power, became his signature.

Final Thoughts on This Essential Album

After the gold rush stands as one of the 1970s’ defining albums.

Neil Young captured a cultural moment while creating timeless art.

The album’s raw production, emotional vulnerability, and thematic depth influenced generations.

From Elliott Smith to contemporary indie artists, Young’s impact remains audible.

The basement recording aesthetic proved that authenticity matters more than production values.

Young’s willingness to embrace imperfection gave countless artists permission to do likewise.

Environmental themes that seemed niche in 1970 now feel urgent and prophetic.

“Southern Man” remains a powerful statement about racial justice and regional responsibility.

The songwriting balances accessibility with poetic ambiguity.

Songs like “Only Love Can Break Your Heart” and “Tell Me Why” became standards.

The album’s critical journey from dismissal to masterpiece proves that initial reception means little.

Great art finds its audience eventually, regardless of contemporary reviews.

After the gold rush requires no special knowledge or context to appreciate.

The emotions Young captured remain universally human.

Loss, love, environmental concern, and social justice transcend any particular era.

This universality ensures the album will resonate for decades to come.

For anyone exploring Neil Young’s extensive catalog, start here.

After the gold rush encapsulates everything that made Young essential while remaining accessible and immediate.

More than fifty years after its release, the album sounds as vital today as in 1970.

The basement tapes Young and David Briggs captured continue speaking truth to each new generation.

After the gold rush remains a masterpiece that redefined what a rock album could achieve.

Neil Young captured a cultural moment while creating timeless art.

The album’s raw production, emotional vulnerability, and thematic depth influenced generations.

From Elliott Smith to contemporary indie artists, Young’s impact remains audible.

The basement recording aesthetic proved that authenticity matters more than production values.

Young’s willingness to embrace imperfection gave countless artists permission to do likewise.

Environmental themes that seemed niche in 1970 now feel urgent and prophetic.

“Southern Man” remains a powerful statement about racial justice and regional responsibility.

The songwriting balances accessibility with poetic ambiguity.

Songs like “Only Love Can Break Your Heart” and “Tell Me Why” became standards.

The album’s critical journey from dismissal to masterpiece proves that initial reception means little.

Great art finds its audience eventually, regardless of contemporary reviews.

After the gold rush requires no special knowledge or context to appreciate.

The emotions Young captured remain universally human.

Loss, love, environmental concern, and social justice transcend any particular era.

This universality ensures the album will resonate for decades to come.

For anyone exploring Neil Young’s extensive catalog, start here.

After the gold rush encapsulates everything that made Young essential while remaining accessible and immediate.

More than fifty years after its release, the album sounds as vital today as in 1970.

The basement tapes Young and David Briggs captured continue speaking truth to each new generation.

After the gold rush remains a masterpiece that redefined what a rock album could achieve.

Add After the Gold Rush to Your Collection

Experience the album that transformed Neil Young into a generational voice and influenced five decades of singer-songwriters.