King Crimson Moonchild: A Controversial Ethereal Magic Ballad Of Freedom!

King Crimson Moonchild remains one of progressive rock’s most audacious experiments – a 12-minute journey that transforms from ethereal ballad into radical free improvisation.

Released on October 10, 1969, this fourth track from In the Court of the Crimson King dedicates nearly a quarter of the album’s entire runtime to unstructured sonic exploration, making it the most controversial piece on prog rock’s most influential debut.

You’re about to discover why this polarizing masterpiece continues to divide listeners over five decades later, and how its groundbreaking approach to silence and space influenced everything from ambient music to modern experimental rock.

When drummer Michael Giles described King Crimson Moonchild as dealing with “time and space” rather than traditional jazz improvisation, he articulated something revolutionary for 1969 rock music.

The song’s appearance in Vincent Gallo’s cult film Buffalo ’66 introduced it to an entirely new generation, with Christina Ricci’s iconic tap dance scene cementing its place in cinema history.

King Crimson Moonchild represents the band at their most fearless – willing to risk commercial appeal for artistic integrity on their very first album.

🎸 Experience King Crimson Moonchild in Audiophile Quality

The 200-gram heavyweight vinyl remaster reveals every subtle nuance of the improvisation.

Hear the delicate interplay between Fripp, McDonald, and Giles as never before.

Limited pressings of this prog rock landmark are selling fast.

📋 Table of Contents [+]

King Crimson Moonchild Overview: Origin Story and Creation

King Crimson Moonchild emerged from a deliberate decision to push the boundaries of what a rock album could contain, recorded on July 31, 1969, at Wessex Sound Studios in London.

The track was conceived after the band had already completed the core material for In the Court of the Crimson King, giving them the freedom to experiment without commercial pressure.

Unlike the meticulously composed pieces elsewhere on the album, King Crimson Moonchild began as what drummer Michael Giles called “a little ditty” before the band “took off into outer space, into nothingness, to see what happened.”

The final album version runs 12 minutes and 9 seconds, though it represents an edited excerpt from an even longer studio improvisation session.

The Writing Process and Inspiration

Peter Sinfield crafted the lyrics for the opening vocal section, drawing from his deep immersion in poetry and fantasy literature.

Sinfield’s influences included William Blake’s visionary mysticism, creating what he described as a “spooky pastoral atmosphere” that was simultaneously eerie and rooted in idyllic, nature-infused reverie.

The lyricist claimed that A Poet’s Notebook by Edith Sitwell significantly influenced his writing, alongside works by Arthur Rimbaud, Paul Verlaine, Kahlil Gibran, and Shakespeare.

Donovan’s opening line from “Colours” proved particularly inspirational, as Sinfield stated it was the defining moment when he realized he had the desire and ability to write songs.

The mystical “moonchild” figure in the lyrics represents innocence, purity, and connection to the subconscious – a being untouched by worldly existence yet dancing on the edge of reality.

Band Context During Recording

The original King Crimson lineup that created Moonchild consisted of Robert Fripp on guitar, Ian McDonald on woodwinds and Mellotron, Greg Lake on bass and vocals, Michael Giles on drums, and Peter Sinfield as lyricist.

By July 1969, the band had already performed their breakthrough concert at Hyde Park opening for the Rolling Stones before an estimated 500,000 people.

The recording sessions at Wessex Sound Studios were remarkably efficient, with King Crimson producing themselves after initial sessions with Moody Blues producer Tony Clarke failed to capture their vision.

Moonchild and its improvised workout were completed in a single day during the July-August 1969 sessions that produced the entire album in just ten days.

💡 Did You Know?

In the original 1969 version of King Crimson Moonchild, Robert Fripp plays a snippet of “The Surrey With the Fringe on Top” from Rodgers and Hammerstein’s Oklahoma! during “The Illusion” section. This playful musical quotation was removed from Steven Wilson’s 2009 remix, cutting approximately 2.5 minutes from the improvisation.

Complete Musical Breakdown of King Crimson Moonchild

King Crimson Moonchild presents the most radical sonic departure on In the Court of the Crimson King, dividing into two dramatically different sections that challenge conventional song structure.

The track runs 12 minutes and 9 seconds in its original album version, with the structured vocal section lasting approximately two and a half minutes before giving way to nearly ten minutes of free-form improvisation.

The Dream vs The Illusion: Two-Part Structure

“The Dream” opens King Crimson Moonchild as a slow, atmospheric ballad driven by Mellotron providing ethereal string and flute textures.

Greg Lake’s gentle vocals float over Ian McDonald’s flute lines while Michael Giles delivers subtle percussion using brushes and light drums.

The transition into “The Illusion” marks one of rock music’s most dramatic shifts – from structured pastoral ballad into completely free-form instrumental exploration.

“The Illusion” represents what Giles described as improvisation that is “not in a jazz way, but is free of structure” – dealing purely with time and space.

The extended improvisation section features light, glowing vibes and moments of quiet deconstruction that anticipate the ambient music movement by decades.

Instrumentation and Performance Details

Ian McDonald’s Mellotron work provides the atmospheric foundation for “The Dream,” creating the foggy, dreamlike soundscape that defines the opening section.

Robert Fripp’s guitar work throughout “The Illusion” demonstrates remarkable restraint, focusing on texture and atmosphere rather than conventional solo playing.

Michael Giles performs a unique alternation between the ride cymbals that music critics specifically praised, creating subtle rhythmic pulses within the free-form structure.

McDonald contributes vibraphone during the improvisation, adding light, glowing tones that shimmer throughout the sonic landscape.

The interplay between all four musicians showcases their ability to communicate musically without predetermined structures or arrangements.

Greg Lake’s bass provides an anchor during the improvisation while allowing maximum freedom for the other instruments to explore.

Vocal Technique and Delivery

Greg Lake delivers the “The Dream” vocals with exceptional softness and delicacy, matching the ethereal quality of Sinfield’s mystical lyrics.

Lake’s rising intonations enhance the dreamlike atmosphere, particularly on phrases that describe the moonchild’s magical activities.

The vocal section demonstrates Lake’s versatility, contrasting dramatically with his powerful delivery on tracks like “Epitaph” and “21st Century Schizoid Man.”

Once “The Illusion” begins, vocals disappear entirely, creating a stark instrumental contrast that emphasizes the shift from verbal poetry to pure sonic exploration.

This absence of vocals in the improvisation section forces listeners to engage with music as abstract sound rather than lyrical narrative.

Recording Sessions and Production Secrets

King Crimson Moonchild was recorded at Wessex Sound Studios in London on July 31, 1969, as part of the intensive sessions that produced In the Court of the Crimson King.

The band made the unusual decision to produce themselves after earlier sessions with Tony Clarke proved unsatisfactory.

Inside the Studio: Recording Sessions

Engineering duties were led by Robin Thompson, assisted by Tony Page, using a 1-inch 8-track recorder that captured the band’s spontaneous creativity.

The improvisation section was recorded as an extended jam, with the final album version being edited down from longer source material.

Peter Sinfield recalled the band’s professional approach to recording sessions, working from lunchtime until exhaustion around nine or ten in the evening without the rock star excess of midnight sessions.

The track was completed in a single day, demonstrating the band’s efficiency and the spontaneous nature of the improvisation.

August 1969 was spent mixing the original eight-track tapes down to two in order to do extensive overdubs on other tracks, though Moonchild’s improvisation section remained largely untouched.

The Art of Free Improvisation

King Crimson Moonchild pioneered the integration of free improvisation into a commercial rock album context, something virtually unheard of in 1969.

The production emphasized capturing the spontaneous interplay between musicians rather than achieving a polished, composed sound.

Giles explained the philosophy behind the improvisation as exploring what happens when you are “just dealing with time and space” without traditional musical structure.

The use of silence as a compositional element within “The Illusion” anticipated techniques that would later define ambient and space rock.

This approach influenced bands like Hawkwind and even Pink Floyd’s extended pieces like “Echoes,” which similarly used silence as melodic material.

The decision to include such radical material on a debut album demonstrated King Crimson’s unwavering commitment to artistic vision over commercial calculation.

King Crimson Moonchild Lyrics: Hidden Meanings Revealed

King Crimson Moonchild presents Peter Sinfield’s most mystical and fantasy-inspired lyrical work, evoking an ethereal, romantic invocation of a magical figure in a dreamlike pastoral landscape.

The lyrics exist only in “The Dream” section, with “The Illusion” being entirely instrumental – a contrast that emphasizes the shift from concrete imagery to abstract experience.

Core Themes and Messages

The central figure of the “moonchild” represents innocence, purity, and a deep connection to the subconscious and natural world.

Sinfield’s imagery places this mystical being in a pastoral landscape filled with rivers, willows, gardens, and fountains – traditional symbols of natural harmony and spiritual renewal.

The moonchild communes with nature, talking to trees and waving silver wands to the night-birds’ song, suggesting a magical being in harmony with the cosmos.

References to “playing hide and seek with the ghosts of dawn” and “waiting for a smile from a sun child” establish a duality between lunar and solar, night and day, dream and waking.

The song explores themes of innocence, fantasy, and the search for a simpler existence untouched by the chaos of modern life.

Peter Sinfield’s Poetic Vision

Sinfield drew from the visionary mysticism of William Blake, whose poetry similarly explored the boundaries between innocence and experience, dream and reality.

The lyrics can be interpreted as a longing for return to childhood innocence, reflecting the late 1960s counterculture’s desire to escape the anxieties of the Vietnam War era.

Some interpretations view the moonchild as representing the creative spirit itself – ethereal, elusive, and existing in a realm beyond ordinary consciousness.

The contrast between the concrete imagery of “The Dream” and the abstract sounds of “The Illusion” suggests that true understanding transcends verbal expression.

Sinfield’s fantasy-tinged imagery connects to the broader sword-and-sorcery aesthetic that would characterize much progressive rock, though rendered here with unusual delicacy.

Chart Performance and Critical Reception

King Crimson Moonchild received mixed responses upon the album’s release in October 1969, with critics praising the ethereal opening while debating the extended improvisation.

The track was never released as a standalone single, with its exposure occurring exclusively within the context of the full album experience.

In the Court of the Crimson King reached number 5 on the UK Albums Chart, spending 18 weeks on the chart, and peaked at number 28 on the US Billboard 200.

The album was certified Gold by the RIAA for equivalent sales of 500,000 units in the United States.

Pete Townshend’s famous endorsement of In the Court of the Crimson King as “an uncanny masterpiece” helped establish its reputation, though contemporary reviews rarely gave Moonchild more than passing mention.

Music critic Mike Barnes noted in his book A New Day Yesterday that “what is rarely ever mentioned about In the Court of the Crimson King is that a quarter of its running time is given over to free improvisation.”

Barnes described King Crimson Moonchild as “both beautifully played and the most adventurous track by a British rock group to date,” while acknowledging that some listeners would skip it like Beatles fans might pass on “Revolution 9.”

Over time, critical appreciation for the track’s experimental qualities has grown, with retrospective analyses recognizing its influence on ambient and experimental rock.

The 2009 Steven Wilson remix brought renewed attention to the track, though the decision to edit approximately 2.5 minutes from “The Illusion” sparked debate among fans.

Cultural Impact and Lasting Legacy

King Crimson Moonchild pioneered the integration of extended free improvisation into progressive rock, establishing a template for sonic experimentation that would influence generations of musicians.

The track’s use of silence and space as compositional elements anticipated the ambient music movement that Brian Eno would later codify.

Artists Influenced by King Crimson Moonchild

Robert Fripp’s later ambient collaborations with Brian Eno can be traced back to the improvisational approach developed on King Crimson Moonchild.

Pink Floyd’s extended improvisational pieces, particularly “Echoes,” demonstrate similar use of silence as melody that Moonchild pioneered.

Space rock bands like Hawkwind made extensive use of the sound design approach that King Crimson Moonchild introduced to rock music.

Progressive rock artists including Porcupine Tree have drawn from King Crimson’s techniques in Moonchild for incorporating spontaneous elements into compositions.

The track has been sampled in electronic music, including works by artists who repurpose its dreamy guitar and atmospheric elements for ambient and downtempo productions.

Buffalo ’66, Covers, and Media Appearances

King Crimson Moonchild gained significant cultural visibility through its use in Vincent Gallo’s 1998 cult film Buffalo ’66.

The iconic scene features Christina Ricci performing a surreal tap dance routine to the opening “Dream” section while a spotlight illuminates her at a bowling alley.

Film critics praised the scene as one of the movie’s most memorable moments, with the dreamlike quality of the music perfectly matching the surreal visual.

The Buffalo ’66 appearance introduced King Crimson Moonchild to an entirely new generation of listeners unfamiliar with progressive rock.

Covers of King Crimson Moonchild remain uncommon outside tribute contexts, with the Flaming Lips among artists who have performed versions emphasizing its improvisational segments.

An abridged version appears on the 1976 compilation A Young Person’s Guide to King Crimson, introducing the track to listeners exploring the band’s catalog.

📢 Discover More King Crimson Classics

Explore our complete 21st Century Schizoid Man analysis, dive into The Court of the Crimson King breakdown, or check out our Epitaph deep dive.

Live Performances: 48 Years in the Making

King Crimson Moonchild was notably absent from the band’s live repertoire throughout the original lineup’s existence in 1969-1970.

The complete version with its extended improvisation was considered too challenging to recreate live, as the studio recording captured a unique spontaneous moment.

The song made its astonishing live debut on October 18, 2017, at Bass Concert Hall in Austin, Texas – 48 years after its original recording.

This first live performance featured the eight-member “Eight Heads in a Duffel Bag” lineup, with guitarist Jakko Jakszyk handling lead guitar during the improvisational sections.

The 2017 live version highlighted how the band approached the improvisation differently than the original, demonstrating that each performance creates a unique musical moment.

King Crimson rehearsed King Crimson Moonchild during 2013-2014 sessions before finally adding it to their concert repertoire.

The extreme rarity of live performances makes any documented version particularly valuable to collectors and fans.

Complete Credits and Personnel

Performed by:

Greg Lake – Lead Vocals, Bass Guitar

Robert Fripp – Guitar

Ian McDonald – Mellotron, Flute, Vibraphone, Keyboards

Michael Giles – Drums, Percussion

Written by:

Robert Fripp – Music

Ian McDonald – Music

Greg Lake – Music

Michael Giles – Music

Peter Sinfield – Lyrics

Production:

King Crimson – Producers (for EG Productions)

Robin Thompson – Recording Engineer

Tony Page – Assistant Engineer

Recording Details:

Recorded: July 31, 1969

Studio: Wessex Sound Studios, London

Album: In the Court of the Crimson King

Label: Island Records (UK), Atlantic Records (US)

Released: October 10, 1969

Length: 12:09 (including “The Dream” and “The Illusion”)

Your King Crimson Moonchild Questions Answered

🎸 Explore More Essential King Crimson Albums

Why King Crimson Moonchild Matters Today

King Crimson Moonchild represents progressive rock at its most uncompromising – a band willing to dedicate a quarter of their debut album to free improvisation when commercial success was far from guaranteed.

The track’s influence extends far beyond prog rock, anticipating ambient music, space rock, and experimental electronic genres by demonstrating that silence and space could be as powerful as sound.

Michael Giles’ philosophical approach to the improvisation – dealing with “time and space” rather than traditional musical structure – articulated ideas that would take decades to fully develop in popular music.

The song’s appearance in Buffalo ’66 proved its timeless appeal, connecting with audiences born decades after its original release through its dreamlike emotional quality.

For listeners willing to embrace its unconventional structure, King Crimson Moonchild offers a meditative experience unlike anything else in rock music – a journey from pastoral beauty into abstract sonic exploration.

King Crimson Moonchild remains essential listening for anyone seeking to understand how progressive rock expanded the boundaries of what popular music could achieve.

Ready to experience King Crimson Moonchild in all its glory?

Grab the remastered edition of In the Court of the Crimson King (200G/Remix/Ltd) or explore our complete guide to King Crimson’s discography!

📖 More King Crimson Deep Dives

Continue your King Crimson journey with these essential reads:

• 21st Century Schizoid Man: Complete Analysis

• The Court of the Crimson King: Ultimate Breakdown

• Epitaph: The Story Behind the Epic

• I Talk to the Wind: Hidden Secrets Revealed

• Starless: King Crimson’s Magnum Opus

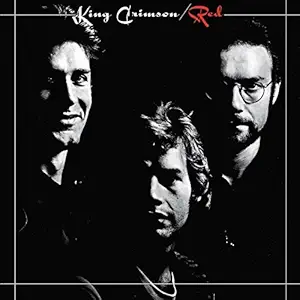

• Red: The Heavy Prog Masterpiece

Sources:

Moonchild (King Crimson song) – Wikipedia

In the Court of the Crimson King – Wikipedia

How We Made In the Court of the Crimson King – Louder Sound

Last updated: January 2026

📱 Share This Article

Hashtags: #KingCrimsonMoonchild #KingCrimson #InTheCourtOfTheCrimsonKing #ProgressiveRock #ClassicRock #ProgRock #GregLake #RobertFripp #IanMcDonald #MichaelGiles #PeterSinfield #Buffalo66 #1969Music #VinylCollector #ClassicAlbums #RockHistory #AmbientMusic #FreeImprovisation