The Neil Young Harvest album stands as one of rock music’s most fascinating paradoxes.

Released on February 15, 1972, this became the best-selling album in the United States that year, topping the Billboard 200 and spawning Young’s only number one single, “Heart of Gold.”

Yet the artist himself famously said it “put me in the middle of the road” and that “traveling there soon became a bore so I headed for the ditch.”

How did an album born from physical pain and romantic inspiration become both Young’s commercial peak and the launching pad for five decades of unpredictable artistic wandering?

Table of Contents

The Sound of Physical Limitation

The Sound of Physical Limitation – How Neil Young’s 1971 back injury at Broken Arrow Ranch forced him to record Harvest sitting down, creating the album’s signature mellow acoustic sound. Image credit: NotebookLM

The mellow, acoustic-driven sound that defines the Neil Young Harvest album wasn’t a calculated commercial strategy. It was a physical necessity born from pain.

In 1971, Young retreated to his newly purchased Broken Arrow Ranch following the breakup of Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young.

While renovating the property, he suffered a severe back injury after picking up a heavy slab of walnut wood.

The injury was so debilitating that he needed back surgery for slipped discs.

“I could only stand about four hours a day,” Young later explained in a 1975 interview.

“I recorded most of Harvest in the brace. I couldn’t physically play an electric guitar.”

This physical limitation forced Young to work sitting down with acoustic instruments.

What could have been a career setback instead shaped one of the most influential albums in rock history.

The album’s pastoral, introspective quality emerged not from artistic pretension but from the practical constraints of a man who could barely stand.

Romance and Inspiration at Broken Arrow

While physical pain shaped the sound, romantic inspiration fueled the songwriting.

Young became infatuated with actress Carrie Snodgress after watching her performance in the film “Diary of a Mad Housewife.”

He was so taken that he arranged to meet her, and she became the primary muse for several Harvest tracks.

Songs like “Heart of Gold,” “Out on the Weekend,” and “A Man Needs a Maid” all drew from this new relationship.

Young’s vulnerability during this period, both physically limited and emotionally open, created the perfect storm for deeply personal songwriting.

The Stray Gators and the Barn

The Stray Gators and the Barn – Neil Young’s Harvest album sessions featuring eccentric Nashville musicians in California and Nashville, where Young demanded extreme simplicity and famously shouted “More Barn!” during playback. Image credit: NotebookLM

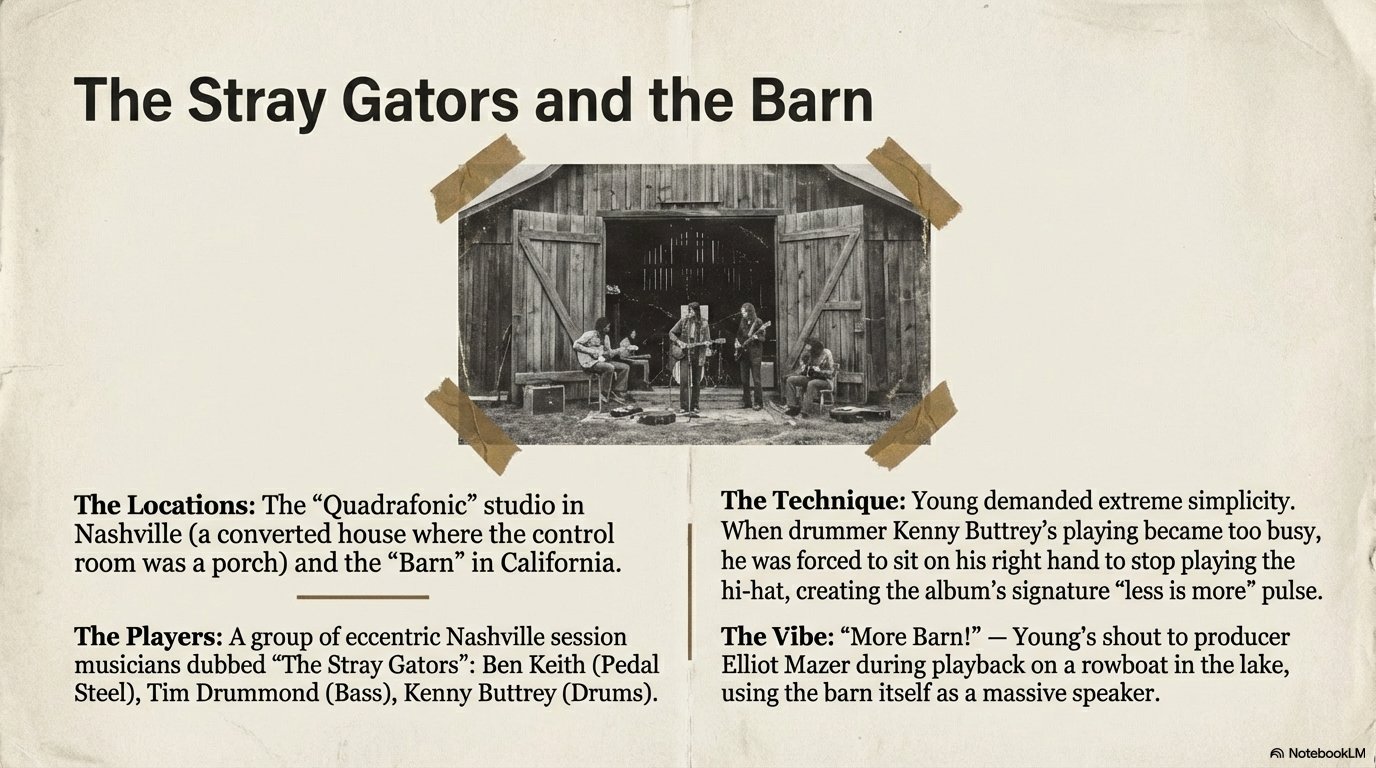

The recording of the Neil Young Harvest album began almost accidentally in Nashville.

After performing on “The Johnny Cash Show,” Young met producer Elliot Mazer, who would become crucial to the album’s creation.

Mazer assembled a group of Nashville session musicians on a Saturday night simply because they were the only players not already working.

Young dubbed this ragtag group “The Stray Gators,” and they became the backbone of Harvest’s sound.

The lineup included Ben Keith on pedal steel guitar, Kenny Buttrey on drums, Tim Drummond on bass, and Jack Nitzsche on piano.

These Nashville pros brought technical excellence, but Young demanded extreme simplicity.

The “Less Is More” Philosophy

Young’s approach to recording bordered on the eccentric.

He directed drummer Kenny Buttrey to play with maximum restraint, stripping away any unnecessary fills or flourishes.

When Buttrey’s hi-hat playing became too busy, Young famously forced the drummer to sit on his right hand to physically prevent him from overplaying.

This “less is more” philosophy extended to the recording environment itself.

Sessions took place at Nashville’s Quadrafonic studio, which was essentially a converted house with a porch serving as the control room.

Young also recorded at his barn in California, using the structure itself as a natural reverb chamber.

The most legendary recording moment came when Young sat in a rowboat on the lake at Broken Arrow Ranch, shouting “More Barn!” to producer Elliot Mazer.

He wanted the barn itself to function as a massive speaker, adding organic ambience to the recordings.

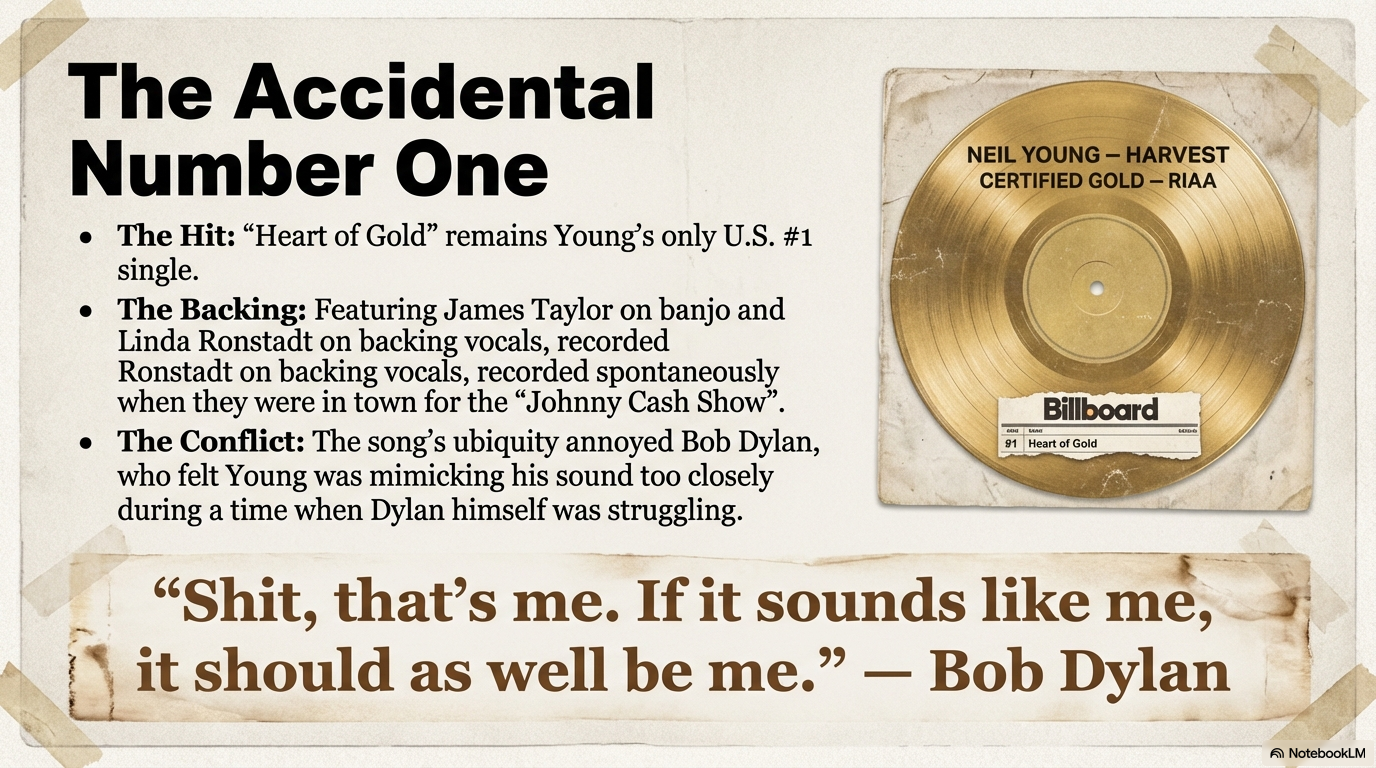

The Accidental Number One

The Accidental Number One – Neil Young’s “Heart of Gold” from Harvest became his only U.S. #1 single, featuring James Taylor and Linda Ronstadt, though its success created tension with Bob Dylan. Image credit: NotebookLM

“Heart of Gold” became the defining song not just of the Neil Young Harvest album but of Young’s entire career.

It remains his only number one single on the U.S. Billboard Hot 100.

The track featured an incredible lineup of talent.

James Taylor played banjo while Linda Ronstadt provided backing vocals.

Both were in Nashville to appear on “The Johnny Cash Show,” and their contributions happened almost spontaneously during the recording sessions.

The Bob Dylan Controversy

The song’s massive success created an unexpected tension with Bob Dylan.

Dylan later admitted he initially hated hearing “Heart of Gold” on the radio.

Why? He felt Young had taken his sound.

During a period when Dylan was struggling commercially with albums like “Self Portrait,” here was Neil Young scoring a massive hit with a song that sounded remarkably Dylan-esque.

“Shit, that’s me,” Dylan reportedly thought when he first heard it.

He felt the harmonica-driven folk-rock sound was so similar to his own style that the song should have been his.

This criticism cut deep, and Young never forgot it.

The commercial triumph that others celebrated became another reason for Young to deliberately avoid repeating the Harvest formula.

For more on Young’s evolution, check out our guide to the complete Neil Young tour schedule.

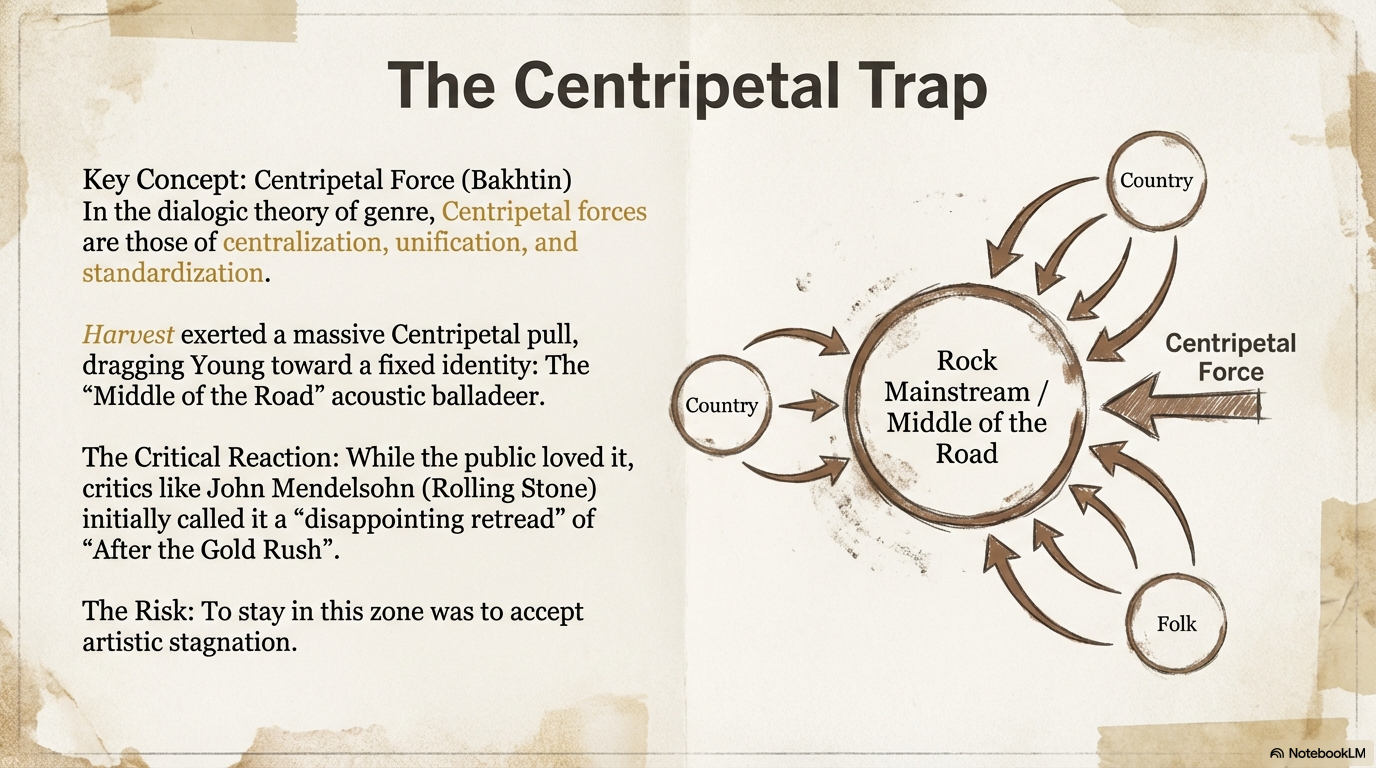

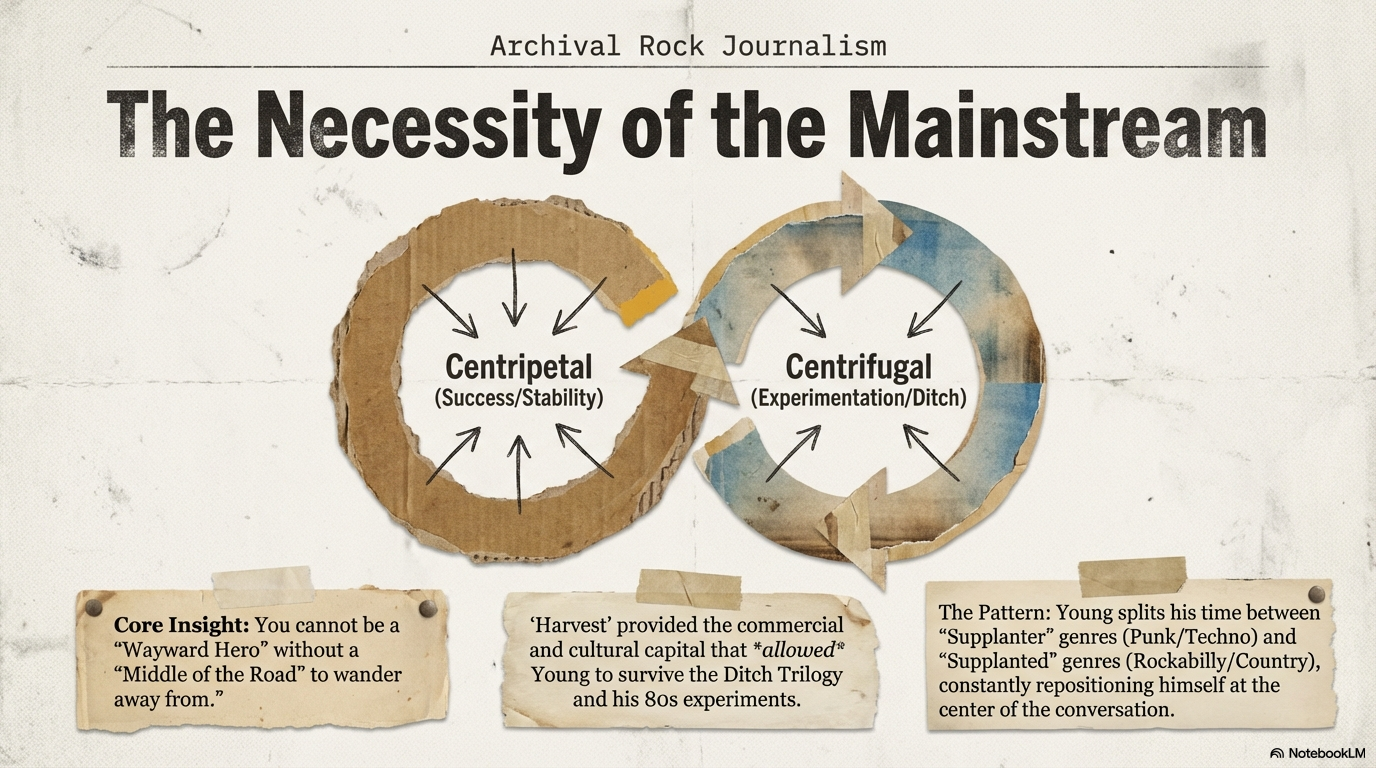

Understanding Waywardness: The Centripetal Trap

The Centripetal Trap – Diagram explaining how Neil Young’s Harvest album success in folk and country genres paradoxically pulled him toward mainstream middle-of-the-road rock, creating the very situation he sought to escape. Image credit: NotebookLM

Music scholar William Echard has developed a fascinating theory to explain the Neil Young Harvest album’s role in the artist’s career.

He calls it the concept of “waywardness,” which describes Young’s habit of wandering broadly while staying within the “rock family.”

Echard identifies two opposing forces at work in Young’s music: centripetal and centrifugal.

Centripetal forces pull Young toward the center, toward mainstream rock success and commercial accessibility.

These forces want to stabilize him, to make him predictable and marketable.

The Neil Young Harvest album represents the ultimate expression of these centripetal forces.

Centrifugal forces, conversely, push Young outward toward the experimental edges of country, blues, electronic music, and punk.

These forces drive his unpredictability and his refusal to repeat himself.

The Paradox of Success

Here’s the trap: by succeeding so massively with Harvest’s folk and country influences, Young found himself pulled toward the mainstream “middle of the road” identity he despised.

The very experimentation that made Harvest interesting became the thing that threatened to cage him.

Rather than accepting this commercial sweet spot, Young deliberately “headed for the ditch.”

His next albums, “Time Fades Away,” “On the Beach,” and “Tonight’s the Night,” formed what fans now call the “Ditch Trilogy.”

These records were deliberately difficult, commercially unsuccessful, and artistically uncompromising.

Young needed to escape the trap that Harvest had created, even if it meant sabotaging his own commercial momentum.

The Geography of Genre

The Geography of Genre – Visual metaphor depicting Neil Young’s Harvest album as navigating between the “Rock Island” and surrounding “genre waters,” illustrating how he maintains rock identity while exploring folk, country, and other musical territories. Image credit: NotebookLM

Echard uses a geographical metaphor to explain Young’s relationship with rock music and other genres.

Imagine rock music as an island, surrounded by various “genre waters” like the Folk Sea, the Country Ocean, the Blues Straits, and the Electronic Archipelago.

The Neil Young Harvest album represents Young sailing into the Country Ocean and the Folk Sea.

But crucially, he never fully leaves the Rock Island behind.

He keeps one foot on shore even as he wades into other musical territories.

This explains why Harvest works so brilliantly.

Young uses country signifiers like pedal steel guitar and Nashville session musicians, but he balances them with counterculture lyrics and rock sensibilities.

He explores folk music’s introspective qualities without abandoning electric guitar entirely.

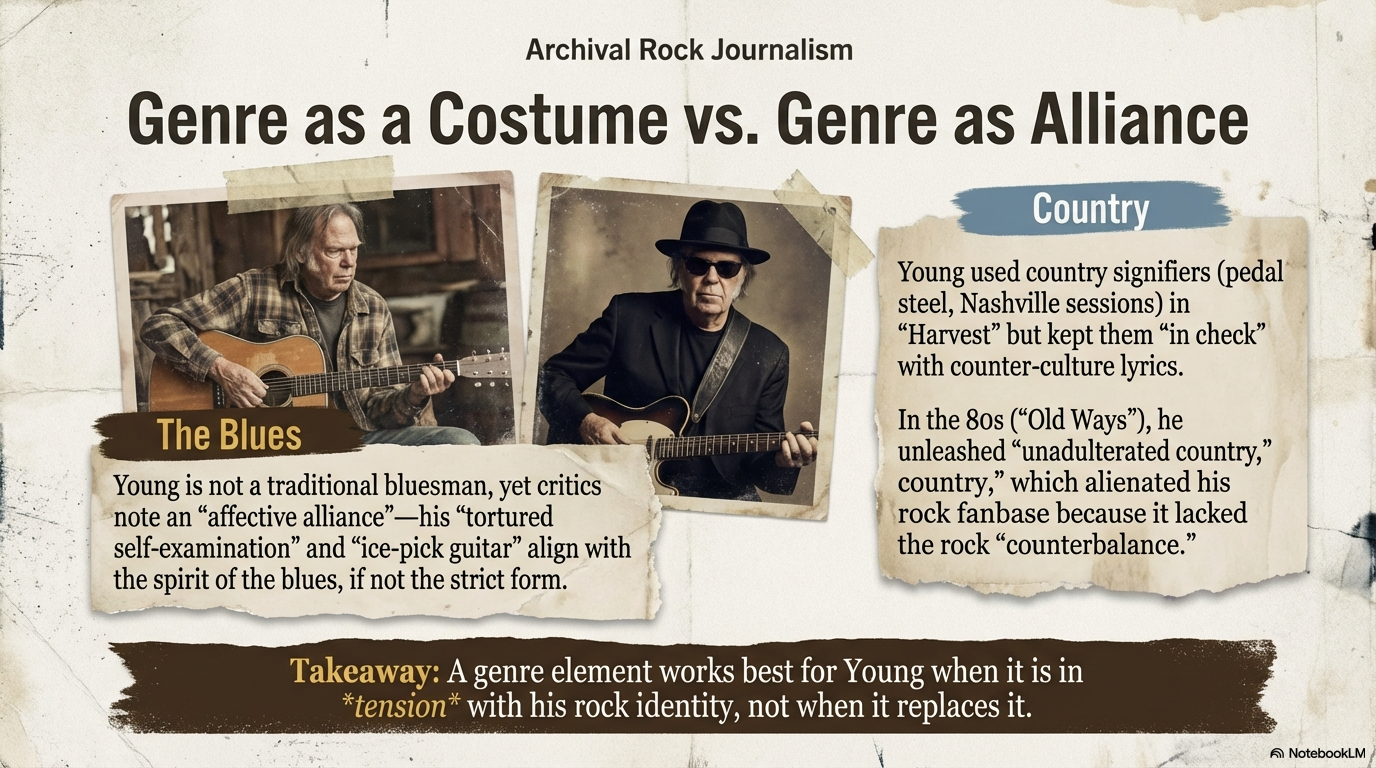

When Genre Becomes Costume

The key insight is that genre works best for Young when it remains in dialogue with his rock identity, not when it replaces it entirely.

Harvest succeeded because it maintained this balance.

Young’s later experiments sometimes failed when he let a genre completely take over.

His 1985 album “Old Ways,” for instance, presented unadulterated country music without the rock counterbalance.

Critics and fans alike rejected it, not because it was poorly executed, but because it felt like Young wearing a costume rather than exploring a facet of his identity.

Blues and Country: Alliance vs. Costume

Genre as a Costume vs. Genre as Alliance – Analysis of Neil Young’s relationship with blues and country genres on Harvest and throughout his career, showing how genre elements work best in tension with his rock identity. Image credit: NotebookLM

Young’s relationship with different genres reveals important truths about the Neil Young Harvest album’s success.

With blues, Young forms what critics call an “affective alliance.”

He’s not a traditional bluesman in technique or form.

But his tortured self-examination and his ice-pick guitar style align perfectly with the blues spirit.

Critics recognize this emotional authenticity even when the formal elements don’t match traditional blues patterns.

With country, the relationship is more complex.

On Harvest, Young used country instrumentation and Nashville musicians, but he kept these elements “in check” with his rock identity and counterculture lyrics.

The pedal steel guitar adds color without dominating.

The Nashville professionalism serves the songs without overwhelming Young’s raw edge.

This balanced approach explains why Harvest remains beloved while later, more committed country experiments like “Old Ways” alienated fans.

Genre elements work best for Young when they exist in productive tension with his core rock identity.

Learn more about this era in our article on Neil Young’s “Heart of Gold” in 1972.

Harvest at 50: The View from the Future

Harvest at 50: The View from the Future – The 50th anniversary box set and Harvest Time documentary reveal the human element behind Neil Young’s best-selling album, showing the camaraderie of The Stray Gators and a 25-year-old artist at his peak. Image credit: NotebookLM

The 2022 release of the Harvest 50th Anniversary Box Set offered new perspective on this landmark album.

The package included the “Harvest Time” documentary, which provides a “rough around the edges” look at the recording process.

These archival materials reveal something crucial: the joy and camaraderie behind the making of the Neil Young Harvest album.

We see a 25-year-old Young at his creative peak, laughing with The Stray Gators in the barn.

We witness the spontaneity and human connection that made these sessions magical.

The Reassessment

Initial reviews of Harvest were surprisingly mixed.

Rolling Stone called it a “disappointing retread,” suggesting Young was coasting on formula rather than innovating.

How wrong that assessment proved to be.

In 2015, Harvest was inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame.

It consistently appears on “greatest albums of all time” lists.

Its influence can be heard in countless alt-country and Americana records that followed.

The critical reassessment reveals how Young’s waywardness confounded contemporary reviewers.

They wanted him to repeat “After the Gold Rush” or to continue evolving in a predictable direction.

Instead, he gave them something that seemed too commercial, too accessible, too mellow.

Only with hindsight did critics recognize that this accessibility was itself a form of rebellion.

Young had taken the commercial route not to sell out, but to create a foundation he could later explode.

The Unmarked Core

Despite Young’s repeated attempts to escape its shadow, the Neil Young Harvest album remains his best-selling work.

It represents what Echard calls the “unmarked core” of Young’s career.

This is the baseline, the center from which all his subsequent experiments are measured.

You cannot understand Young’s punk phase without Harvest.

You cannot appreciate his electronic experiments without this acoustic foundation.

You cannot grasp his return to country without recognizing how Harvest did it first, and better.

The album Young tried to escape became the very thing that enabled his freedom.

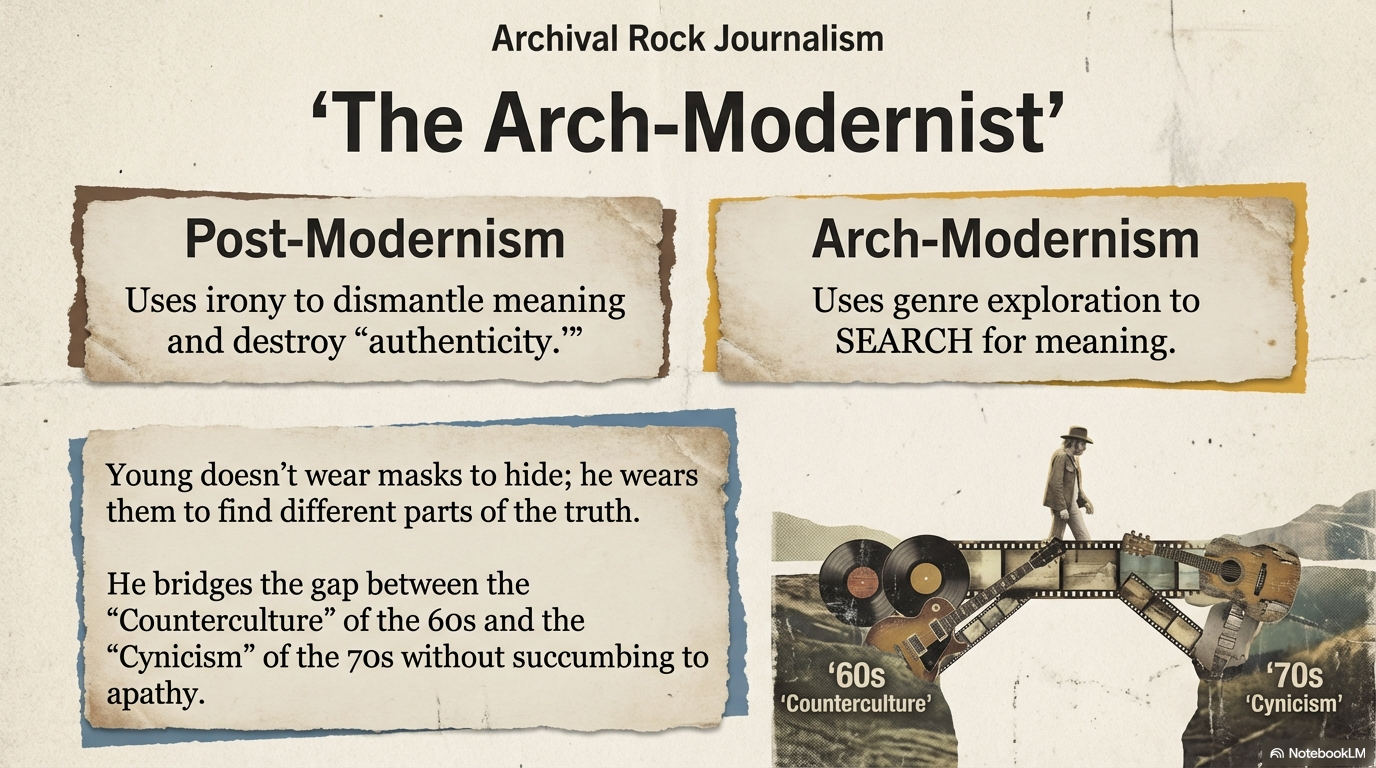

The Arch-Modernist

‘The Arch-Modernist’ – Theoretical framework explaining Neil Young’s unique position using genre exploration to search for meaning rather than postmodern irony, bridging the gap between 60s counterculture idealism and 70s cynicism without succumbing to apathy. Image credit: NotebookLM

Echard proposes that Young represents a unique artistic philosophy he calls “arch-modernism.”

This stands in direct contrast to the postmodernism that dominated later decades.

Postmodernism uses irony to dismantle meaning and destroy claims to authenticity.

Arch-modernism, as embodied by Young, uses genre exploration to actively search for meaning.

Young doesn’t wear different genre masks to hide or to play games with his audience.

He wears them to find different parts of truth.

Each stylistic shift represents a genuine attempt to locate meaning in a particular musical tradition.

Bridging the Cultural Divide

The Neil Young Harvest album appeared at a crucial cultural moment.

It bridged the gap between the counterculture optimism of the 1960s and the cynicism of the 1970s.

The album contains remnants of 60s idealism in its search for “heart of gold” and emotional authenticity.

But it also acknowledges the darker realities emerging in the 70s: addiction (“The Needle and the Damage Done”), political disillusionment (“Alabama”), and personal isolation.

Young refused to succumb to apathy or ironic detachment.

Instead, he kept searching through different musical styles and emotional registers.

This earnest quest for meaning, even when it led to difficult or uncommercial places, defines Young’s artistic project.

Harvest provided the commercial foundation that allowed this search to continue for five decades.

The Necessity of the Mainstream

The Necessity of the Mainstream – Circular diagram illustrating how Neil Young’s Harvest album commercial success provided the financial and cultural capital that allowed him to survive the experimental Ditch Trilogy and radical 80s genre explorations. Image credit: NotebookLM

Here’s the ultimate paradox of the Neil Young Harvest album: you cannot be a wayward hero without a middle of the road baseline to wander from.

Young needed Harvest’s commercial success to survive his subsequent experiments.

The Ditch Trilogy albums were commercial failures that could have ended his career.

His 1980s experiments with rockabilly, synthesizers, and hard rock confused fans and label executives alike.

But because he had the massive commercial and cultural capital from Harvest, Young could afford these risks.

The album he claimed put him “in the middle of the road” actually funded his journey into the ditch.

The Perpetual Cycle

Echard notes that Young oscillates between what he calls “supplanter” and “supplanted” genres.

Supplanter genres like punk and techno were actively challenging rock’s dominance.

Supplanted genres like rockabilly and traditional country were being overtaken by rock.

Young engaged with both types, constantly repositioning himself at the center of cultural conversation.

But he could only do this because Harvest had established him as a legitimate rock artist with mainstream credibility.

The centripetal and centrifugal forces don’t oppose each other in Young’s career.

They work together in a perpetual cycle.

Harvest pulls toward the center, creating stability and commercial success.

This success then enables the centrifugal experiments that push outward toward the edges.

Those experiments eventually create nostalgia for the center, leading to periodic returns to more accessible sounds.

The cycle continues because Harvest established the pattern.

For insights into Young’s current work, read about his 2026 tour plans.

The Ongoing Dialogue

“The Ongoing Dialogue” – Final analysis revealing how Neil Young’s Harvest album served as the essential anchor while the Ditch represented his artistic journey, with his genius lying in maintaining dialogic tension between commercial accessibility and experimental risk-taking. Image credit: NotebookLM

The Neil Young Harvest album was the anchor.

The ditch was the journey.

And Young’s genius lies not in mastering one sound, but in maintaining the dialogic tension between them.

As William Echard explains, Young was expected to surprise his audience.

His stylistic diversity became recognized as a mark of authorial integrity rather than artistic confusion.

Fans learned to trust that wherever Young wandered, he was following an authentic creative impulse rather than a commercial calculation.

This trust was earned through Harvest’s success and Young’s immediate willingness to abandon it.

By “heading for the ditch” right after his biggest commercial triumph, Young proved that success wouldn’t tame him.

This paradoxically gave him permission to be occasionally commercial again, because fans knew he would never stay there.

Five Decades of Waywardness

The pattern established in 1972 has continued for over fifty years.

Young still oscillates between accessible folk-rock and experimental noise, between acoustic introspection and electric bombast.

Albums like “Harvest Moon” (1992) explicitly referenced the original Harvest sound, showing Young willing to revisit his commercial peak when it served the songs.

But he never stayed in that territory for long, following it with albums that challenged and confused his audience once again.

The Neil Young Harvest album made this entire career possible.

It provided the baseline that defines waywardness itself.

Without a center, there can be no wandering.

Without the road, there can be no ditch.

Harvest gave Young both: a commercial and artistic center to define himself against, and the freedom to explore everything else.

The Legacy Lives On

When we look back at the Neil Young Harvest album today, we see more than just a successful 1972 record.

We see the foundation of one of rock music’s most remarkable careers.

Born from physical pain and romantic inspiration, recorded in unconventional spaces with ragtag musicians, and released to massive commercial success that its creator immediately fled from, Harvest embodies every contradiction that makes Neil Young fascinating.

It’s an album that sounds mellow and accessible on the surface but contains depths of meaning that scholars still unpack today.

It’s a commercial triumph that enabled decades of commercial failures.

It’s a wayward masterpiece that established the very baseline it sought to escape.

More than fifty years later, the dialogue between Harvest and the ditch continues.

Young still navigates between centripetal and centrifugal forces, still searches for meaning through genre exploration, still surprises audiences by following his muse wherever it leads.

And it all began with a back brace, a barn, and a reluctant journey to the middle of the road that paradoxically led to the most interesting ditches in rock history.

The Neil Young Harvest album remains essential listening not despite its contradictions, but because of them.